Category: C.S. Lewis

Gene Edward Veith on The Key to C.S. Lewis

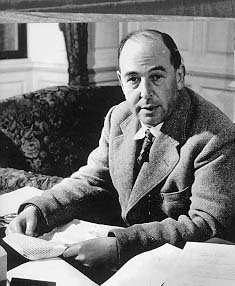

C.S. Lewis was not only a Christian apologist and lay theologian. He was also an unusually imaginative and creative novelist. And in his day job at Oxford and then Cambridge he was an astonishingly perceptive and influential literary scholar.

At a time when the modernist literary establishment was obsessed with depressingly bleak realistic fiction, Lewis sent readers’ imaginations soaring in his Chronicles of Narnia. While the modernists were looking down their noses at popular genre fiction, Lewis was writing the provocative

science fiction of his Space Trilogy.

In his apologetic and theological writing, Lewis was surprising both non-believers and emotional pietists in applying lucid, logical thinking to argue that Christianity is actually true. In his fiction, though, Lewis opposed the dull rationalism of his age to provoke in his readers feelings of wonder, mystery, and longing.

In his literary scholarship, Lewis taught modern readers, inhibited by the blinders of their own narrow little time, how to respond to allegory (The Allegory of Love), how to understand Milton (Preface to Paradise Lost), how to appreciate ancient cosmology (The Discarded Image), and how to read for pleasure (An Experiment in Criticism).

In his breath-takingly comprehensive volume in The Oxford History of English Literature, with the daunting title English Literature in the Sixteenth Century (Excluding Drama), Lewis not only discusses apparently every work written in that century, he develops the notion that there are two styles of poetry: the golden and the drab. Golden verse employs beautiful language to evoke the transcendent. Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton are golden. Drab verse employs colloquial, unadorned language to evoke the cynical and down-to-earth. Donne and most poets currently in vogue are drab. In other writings, Lewis defends Shelley (the atheist) for his golden verse, while critiquing John Donne and T.S. Eliot (his fellow Anglican Christians) for their drabness.

The point here is that Lewis was a complex thinker with a wide-ranging sensibility. He was both logical and wildly imaginative, conservative and a non-conformist, a devout Christian whose faith was never stodgy or limiting, but stimulating and liberating. And I think I have found the key to understanding Lewis in all of his complexities and in all of his different kinds of writing.

Not long after he became a Christian, Lewis wrote about his conversion in an odd book entitled Pilgrim’s Regress. An allegory, like John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, it depicts an everyman named John who reflects Lewis’ own spiritual journey. He leaves his childhood home, Puritania, rebelling against its rules and restrictions, just as Lewis left behind his protestant upbringing in Northern Ireland. Just as young Lewis did, John falls in with characters like Mr. Sensible and Mr. Humanist and faces the temptations of the spirit of the age (Freudianism, Marxism), as well as moral temptations (the Brown Girls, symbolizing lust, and the Clevers, symbolizing worldliness). All along, John has glimpses of a far-away island, which fills him with transcendent longing, just as Lewis describes in his memoir Surprised by Joy.

Eventually, through the mysterious leading of the “Man” (Christ), John comes to accept the Landlord (God) and is received by Mother Kirk (the church). But he still must travel a narrow path, avoiding both the the arid rocks on the North (symbolizing rationalism) and the fetid swamps on the South (symbolizing emotionalism). Eventually, he arrives at where he began, the faith of his childhood at Puritania, which he now recognizes was not about rules and restrictions at all, but grace and faith. He then, like Bunyan, crosses the waters into the everlasting life beyond.

Pilgrim’s Regress is an odd book for many people, but it has always been one of my favorites. Its deft portrayals of different philosophies and worldviews are insightful and illuminating. More than that, the book is an evocative fantasy — giants, dragons, and adventure — of the sort that Lewis later would develop so thoroughly in The Chronicles of Narnia. And everything that Lewis would write is summed up in the book’s subtitle: “An Allegorical Apology for Christianity, Reason, and Romanticism.”

The phrase seems strange. The words do not seem to go together. Are not reason and romanticism opposites? The Enlightenment’s Age of Reason was countered, at least for a while, with Romanticism’s Age of Emotion. And did not both movements oppose Christianity? And yet, it is true that all three need to be defended, since they are all three under attack. Today, even more than in Lewis’ time, our culture rejects not only reason but objective truth altogether. Romantic idealism has been replaced with cynicism and nihilism. True, both rationalism and romanticism, by themselves, lead to falsehoods and dead ends. But there is a legitimate use of reason and of emotion. And Christianity is the only world view big enough to account for them both.

Christianity offers not only a world view but a sensibility, a way to think and to feel. Lewis addresses both the head and the heart. He is an apologist for reason, romanticism, and — what holds them together — Christianity.

ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED ON JANUARY 1ST, 2008 IN TABLE TALK MAGAZINE: http://www.ligonier.org/learn/articles/key-cs-lewis/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Gene Edward Veith is academic dean of Patrick Henry College in Purcellville, Virginia, and director of the Cranach Institute at Concordia Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri.

Dan DeWitt on The Tale of C.S. Lewis’ Imaginative Legacy

C.S. Lewis is to evangelicalism what Elvis is to rock music. It is doubtful that you will find a multitude of Lewis impersonators if you visit Las Vegas; it would certainly be comical if you did, but in the same way that Elvis is an unavoidable figure in the history of American pop culture, you cannot talk about Christianity in the 20th century without mentioning Clive Staples Lewis.

Lewis scholar Colin Duriez calls Lewis an enigmatic figure that evangelicals often recreate in their own image. But even granting this unfortunate tendency to tailor Lewis according to our own Sitz im Leben, what is it that makes him such a perennial candidate for our own projections? We are content to bury most Oxford dons of the past beneath a dusty blanket of apathetic forgetfulness. Why should Lewis be any different?

Lewis scholar Colin Duriez calls Lewis an enigmatic figure that evangelicals often recreate in their own image. But even granting this unfortunate tendency to tailor Lewis according to our own Sitz im Leben, what is it that makes him such a perennial candidate for our own projections? We are content to bury most Oxford dons of the past beneath a dusty blanket of apathetic forgetfulness. Why should Lewis be any different?

There were certainly better theologians than Lewis. He would agree with this. He never claimed to be a theologian, of this he reminds us in almost all of his theological writings, perhaps to the point of overemphasis. Yet most lists of the top theologians of all time include C.S. Lewis. Why this disparity between his claim as a mere layperson, and our desire to elevate him among theological heavyweights like Augustine and John Calvin?

Perhaps Lewis’ legacy is a result of his scholarship. But even though he was busy working on his magnum opus, The Oxford History of English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Timemagazine, in its 1947 cover article on Lewis, said his colleagues frowned upon him because he spent so much time writing outside of his own discipline; an academic faux pas if there ever was one. And most people today have never even heard of his scholarly works like his OHEL project, or Medieval and Renaissance Literature or the Allegory of Love.

In her The New York Times article, “C.S. Lewis, Evangelical Rock Star,” journalist T.M. Luhrmann suggests that it is Lewis’ impact on the imagination that makes his influence timeless. In a progressively secular culture that places an ever-lowering premium on non-empirical values, Lewis offers us a way to envision the love of God via Aslan, the not-safe-yet-good lion of Narnia. In her article, Luhrmann recounts the story of Bob, a man deeply wounded by his church experience. “What Aslan gave Bob,” she writes, “was a sense that God was real and loved him.”

Bob is not alone. Lewis afforded this same vision to many. Not everyone, however, is as welcoming of Aslan’s request that by knowing him in Narnia for a little while they might come to know him better in their own world. Alas, Lewis’ creative blade cuts both ways.

That’s why Laura Miller, an award-winning writer and a self-proclaimed skeptic, says she found great offense when, as an adult, she re-read her favorite childhood series. In her work, The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia, she writes, “I was horrified to discover that the Chronicles of Narnia, the joy of my childhood and the cornerstone of my imaginative life, were really just the doctrines of Christianity in disguise.” She’s right and wrong. Lewis smuggles theology behind enemy lines, make no doubt, but he does more than that: he opens a window into our world as well.

In the Chronicles, Lewis offers a commentary of a parallel reality. He says something real, something tangible and palpable even, but he says it through the mouth of a talking fawn and through the roar of a beastly lion. And he did it in such a way as to bring the reader face-to-face with the actual world. And the more someone understands Lewis’ gospel incarnated in the land of Narnia, the more he or she either loves or spurns the savior figure, who inVoyage of the Dawn Treader turns from a lamb into a lion right before the children’s eyes.

Michael Ward, editor of The Cambridge Companion to C.S. Lewis, believes the connection to our world goes deeper than the Christ-like symbolism found in Aslan. Ward offers a framework for understanding the flow and emphases of the Narnia stories rooted in Lewis’ life-long love of medieval literature.

In his book Planet Narnia, Ward builds a compelling case that Lewis deployed an unspoken theme — the seven medieval planets — as the substructure of the Chronicles of Narnia. Ward suggests a coherent system for what is otherwise, to be completely honest, a randomly ordered collection of stories. But Ward does more than this, if he is right. If Lewis was using a medieval cosmology to frame the narrative, this further illustrates — powerfully so in my opinion — how Lewis sought to tether the truths embedded in the children’s stories back to our universe. He was dropping breadcrumbs along the Narnian path to help us find our way back home.

Colin Duriez likens Lewis to another creator of an imaginary world, John Bunyan. This comparison is fitting for several reasons. For starters, Lewis’ first literary account of his conversion is found in his book, The Pilgrim’s Regress. He wrote the allegorical account of his journey to faith in a little over a week’s time while visiting his best friend from childhood, Arthur Greeves.

As the title reflects, the theme is borrowed from Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, but the focus is not a burden to be relieved, but rather, a joy to be realized. That’s why it is a regress in contrast to Bunyan’s progress.

In the words from the opening of G.K. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man, “There are two ways of getting home; and one of them is to stay there. The other is to walk round the whole world till we come back to the same place.” Lewis traveled round the intellectual world only to arrive back home on the shores of the Christian gospel.

Another reason the Bunyan connection is appropriate is because The Pilgrim’s Progress leads readers to imagine and feel the weight of truths that so often, when presented in clear didactic methods, turn grey and blend in as ambient background noise. Through the use of story, Bunyan struck an imaginative chord that still resonates with the human experience today. Lewis did the same.

There are a lot of theories as to why Lewis changed his methodology after the publication of Mere Christianity to a nearly exclusively fictional format. There was the G.E.M. Anscombe debate that allegedly shook Lewis’ apologetic approach. There certainly must have been fatigue from years of publicly defending the gospel. But I think the real culprit is that Lewis found his preferred avenue for making an indelible mark on the mind of his readers.

In a letter to Carl F.H. Henry, as to why he wouldn’t write articles for Christianity Today, Lewis said, “My thought and talent (such as they are) now flow in different, though I trust not less Christian, channels, and I do not think I am at all likely to write more directly theological pieces. The last work of that sort which I attempted had to be abandoned. If I am now good for anything it is for catching the reader unaware — thro’ fiction and symbol. I have done what I could in the way of frontal attacks, but I now feel quite sure those days are over.”

The theological work Lewis mentioned to Henry was a book on prayer. He described the challenge of completing this book in several of his letters with others and even in a conversation with D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones when they shared a boat ride from England to Ireland. “When will you write another book like Mere Christianity?” Jones asked. “When I discover the meaning of prayer,” Lewis responded.

Lewis did finally finish the book on prayer, six months before he died. But it wasn’t anything like he originally set out to do. The whole project came together, after years of difficulty, when he placed it in the context of an imaginary conversation with a fictional character named Malcome. It was published the year after he died as Letters to Malcome: Chiefly on Prayer. It was the last book C.S. Lewis wrote before his death 50 years ago.

The fact that it came together as fiction is an illustration of Lewis’ lasting legacy. As Chesterton once said, “We must invoke the most wild and soaring sort of imagination; the imagination that can see what is there.” Lewis could see what is there, and he continues to help others see it as well, even five decades after his death.

Lewis concluded his essay, “Is Theology Poetry?” with these words: “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it but because by it I see everything else.” Through the gospel, Lewis could see everything else. And his books invite us to do the same. But this is a task that requires a healthy dose of imagination.And that’s why I believe Lewis continues to be such a wonderful and timeless guide.

Article Originally Appeared at: http://www.sbts.edu/blogs/2013/11/20/the-tale-of-c-s-lewis-imaginative-legacy/

About the Author:

Dan DeWitt serves as dean of Boyce College. He is the author of the forthcoming book Jesus or Nothing, and editor of A Guide to Evangelism. You can connect with DeWitt through his website or on twitter.

Joe Carter on 9 Things You Should Know About C.S. Lewis

Today is the 50th anniversary of the death of Clive Staples Lewis, one of the most well known, widely read, and often quoted Christian author of modern times. Here are nine things you should know about the author and apologist who has been called “The Apostle to the Skeptics.”

1. Lewis is best known for his seven children’s books, The Chronicles of Narnia. But he wrote more than 60 books in various genres, including poetry, allegorical novel, popular theology, educational philosophy, science-fiction, children’s fairy tale, retold myth, literary criticism, correspondence, and autobiography.

1. Lewis is best known for his seven children’s books, The Chronicles of Narnia. But he wrote more than 60 books in various genres, including poetry, allegorical novel, popular theology, educational philosophy, science-fiction, children’s fairy tale, retold myth, literary criticism, correspondence, and autobiography.

2. Lewis’s close friend Owen Barfield, to whom he dedicated his book The Allegory of Love, was also his lawyer. Lewis asked Barfield to establish a charitable trust (“The Agape Fund”) with his book earnings. It’s estimated that 90 percent of Lewis’s income went to charity.

3. Lewis had a fondness for nicknames. He and his brother, Warnie, called each other “Smallpigiebotham” (SPB) and “Archpigiebotham” (APB), inspired by their childhood nurse’s threat to smack their “piggybottoms.” Even after Lewis’s death, Warnie still referred to him as “my beloved SPB.”

4. In 1917, Lewis left his studies to volunteer for the British Army. During the First World War, he was commissioned into the Third Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry. Lewis arrived at the front line in the Somme Valley in France on his nineteenth birthday and experienced trench warfare. On 15 April 1918, he was wounded and two of his colleagues were killed by a British shell falling short of its target. Lewis suffered from depression and homesickness during his convalescence.

5. Lewis was raised in a church-going family in the Church of Ireland. He became an atheist at 15, though he later described his young self as being paradoxically “very angry with God for not existing.”

6. Lewis’s return to the Christian faith was influenced by the works of George MacDonald, arguments with his Oxford colleague and friend J. R. R. Tolkien, and G. K. Chesterton’sThe Everlasting Man.

7. Although Lewis considered himself to an entirely orthodox Anglican, his work has been extremely popular among evangelicals and Catholics. Billy Graham, who Lewis met in 1955, said he “found him to be not only intelligent and witty but also gentle and gracious.” And the late Pope John Paul II said Lewis’ The Four Loves was one of his favorite books.

8. After reading Lewis’ 1940 book, The Problem of Pain, the Rev. James Welch, the BBC Director of Religious Broadcasting, asked Lewis to give talks on the radio. While Lewis was at Oxford during World War II he gave a series of BBC radio talks made between 1942 and 1944. The transcripts of the broadcasts originally appeared in print as three separate pamphlets — The Case for Christianity (1942), Christian Behaviour (1943), and Beyond Personality (1944) — but were later combined into the book, Mere Christianity. In 2000,Mere Christianity was voted best book of the twentieth century by Christianity Today.

9. On 22 November 1963, exactly one week before his 65th birthday, Lewis collapsed in his bedroom at 5:30 pm and died a few minutes later. Media coverage of his death was almost completely overshadowed by news of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, who was killed less than an hour earlier. In 2003, Lewis was added to the list of saints commemorated on the church calendar of the Episcopal Church.

Article originally posted at: http://thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/tgc/2013/11/22/9-things-you-should-know-about-c-s-lewis/

R.C. Sproul on C.S. Lewis and The Weight of Glory

“The Weight of Glory” by Dr. R.C. Sproul

C.S. Lewis emerged as a twentieth-century icon in the world of Christian literature. His prodigious work combining acute intellectual reasoning with unparalleled creative imagination made him a popular figure not only in the Christian world but in the secular world as well. The Chronicles of Narnia and The Space Trilogy, though rife with dramatic Christian symbolism, were devoured by those who had no interest in Christianity at all, but were enjoyed for the sheer force of the drama of the stories themselves. An expert in English literature, C.S. Lewis functioned also as a Christian intellectual. He had a passion to reach out to the intellectual world of his day in behalf of Christianity. Through his own personal struggles with doubt and pain, he was able to hammer out a solid intellectual foundation for his own faith. C.S. Lewis had no interest in a mystical leap of faith devoid of rational scrutiny. He abhorred those who would leave their minds in the parking lot when they went into church. He was convinced that Christianity was at heart rational and defensible with sound argumentation. His work showed a marriage of art and science, a marriage of reason and creative imagination that was unparalleled. His gift of creative writing was matched by few of his twentieth-century contemporaries. His was indeed a literary genius in which he was able to express profound Christian truth through art, in a manner similar to that conveyed by Bach in his music and Rembrandt in his painting. Even today his introductory book on the Christian faith — Mere Christianity — remains a perennial best seller.

We have to note that although a literary expert, C.S. Lewis remained a layman theologically speaking. Indeed, he was a well-read and studied layman, but he did not benefit from the skills of technical training in theology. Some of his theological musings will indicate a certain lack of technical understanding, for which he may certainly be excused. His book Mere Christianity has been the single most important volume of popular apologetics that the Christian world witnessed in the twentieth century. Again, in his incomparable style, Lewis was able to get to the nitty-gritty of the core essentials of the Christian faith without distorting them into simplistic categories.

His reasoning, though strong, was not always technically sound. For example, in his defense of the resurrection, he used an argument that has impressed many despite its invalidity. He follows an age-old argument that the truth claims of the writers of the New Testament concerning the resurrection of Jesus are verified by their willingness to die for the truths that they espoused. And the question is asked: Which is easier to believe — that these men created a false myth and then died for that falsehood or that Jesus really returned from the grave? On the surface, the answer to that question is easy. It is far easier to believe that men would be deluded into a falsehood, in which they really believed, and be willing to give their lives for it, than to believe that somebody actually came back from the dead. There has to be other reasons to support the truth claim of the resurrection other than that people were willing to die for it. One might look at the violence in the Middle East and see 50,000 people so persuaded of the truths of Islam that they are willing to sacrifice themselves as human suicide bombs. History is replete with the examples of deluded people who have died for their delusions. History is not filled with examples of resurrections. However, despite the weakness of that particular argument, Lewis nevertheless made a great impact on people who were involved in their initial explorations of the truth claims of Christianity.

To this day, people who won’t read a Bible or won’t read other Christian literature will pick up Mere Christianity and find themselves engaged by the acute mental processes of C.S. Lewis. The church owes an enormous debt to this man for his unwillingness to capitulate to the irrationalism that marked so much of Christian thought in the twentieth century — an irrationalism that produced what many describe as a “mindless Christianity.”

The Christianity of C.S. Lewis is a mindful Christianity where there is a marvelous union between head and heart. Lewis was a man of profound sensitivity to the pain of human beings. He himself experienced the crucible of sanctification through personal pain and anguish. It was from such experiences that his sensitivity developed and his ability to communicate it sharply honed. To be creative is the mark of profundity. To be creative without distortion is rare indeed, and yet in the stories that C.S. Lewis spun, the powers of creativity reached levels that were rarely reached before or since. Aslan, the lion in The Chronicles of Narnia, so captures the character and personality of Jesus; it is nothing short of amazing. Every generation, I believe, will continue to benefit from the insights put on paper by this amazing personality.

Article: Originally posted on January 1, 2008 in Table Talk Magazine http://www.ligonier.org/learn/articles/weight-glory/

C.S. Lewis and His Legacy: An Interview with Christopher Mitchell

What do you think the most important aspect of C.S. Lewis’s legacy is?

From a historical perspective, the most important legacy of Lewis is as an advocate of the Christian faith. There are other things to be said that were important: he was a great writer, a great literary critic, literary historian, a great writer of children’s fantasy literature. But at the center of his being after he became a Christian was a desire to promote Christianity. He wanted to clear away the intellectual prejudices against it and to expose fallacies in the objections to it. He sought to clear away the intellectual rubble and prepare minds and the imagination to receive the Christian message.

What made Lewis’s approach unique, though, was the way he brought together the intellect and the imagination. He was brilliant at finding illustrations and metaphors that got to the heart of the matter, and those are ways of writing that engage both hearts and minds simultaneously. J.I. Packer once observed both lobes of Lewis’ brain were so thoroughly developed “that he was as strong in fantasy and fiction as he was in analysis and argument. That made him in his day, and makes him still, a powerful and haunting communicator in both departments.”

And it struck people as unique even in his own time, when theology was generally considered a musty, irrelevant subject. In 1944, the Times Literary Supplement said that observed: “Mr. Lewis has a quite unique power of making Theology attractive, exciting and (one might almost say) an uproariously fascinating quest.” Only three years later, Time would call him the one of the most influential spokesman for Christianity in the English-speaking world and said he had a “talent for putting old-fashioned truths into a modern idiom” and giving “a strictly unorthodox presentation of strict orthodoxy.”

Where are the C.S. Lewis’s of today? Do you think we should look for another?

That’s a question that I’ve been asked routinely for the past two decades. People want to know who is doing for our generation what Lewis did for his. But I never remember being asked where the Augustines, the Luthers, the Bunyans, the Dantes are. The deep hunger for more of what Lewis had to offer is very real.

I think expecting the same unique combination of intellect and imagination is probably asking too much. It’s easy to find people who can do one or the other, but bringing them together as Lewis did is extraordinary. God never leaves his people without a witness and there are plenty of individuals who are today working creatively and engagingly on one side of the equation or the other.

What do you think those who admire the legacy of Lewis should do next?

For more than a decade I have been saying that if a person were to simply read the books C.S. Lewis mentions in his autobiography, Surprised By Joy, they would receive a first rate education. Milton, Aristotle, Dante, George Bernard Shaw and G.K. Chesterton–they all make an appearance in one way or the other. The exercise of having to think through and to digest the thinking of others is the first step in our training to think through a thing for ourselves.

In the course of my nearly twenty-years as Director of the Wade Center, and now as a Professor at Biola’s Torrey Honors Institute, I have seen the enormous educational and spiritual value of a broad and deep reading of critical works of literature over a wide range of topics, periods, and cultures alongside an equally critical reading of biblical texts.

I also think we should be on constant guard against what C.S. Lewis famously called “chronological snobbery,” or the conviction that the thinking of the past no longer holds any real significance for the present. Deepening our knowledge of how people from previous generations thought helps us discern and avoid our own blind spots. And it helps in the face of the challenges of globalization, too. Encountering thinking from the diverse cultures and ages of the past places us in a position to think openly and rightly about contemporary situations that are different from our own context.

Dr. Christopher Mitchell is Associate Professor at Biola University’s Torrey Honors Institute. He was Director of the Marion E. Wade Center, which is devoted to supporting the legacy of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and others for nearly twenty years. Interview originally appeared on Trinity Forum’s Website: http://www.ttf.org/cs-lewis-and-his-legacy-interview-christopher-mitchell

Sinclair Ferguson: Remembering C.S. Lewis – On The 50-Year Anniversary of His Death

WHO WAS C.S. LEWIS?

November 22, 1963, the date of President Kennedy’s assassination, was also the day C.S. Lewis died. Seven years earlier he had thus described death: “The term is over: the holidays have begun. The dream is ended: this is the morning.” The metaphor inherent in these words is striking. It comes from the world of students and pupils, but only a teacher would employ it as a metaphor for death. The words (from The Last Battle) bring down the curtain — or perhaps better, close the wardrobe door — on Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia. But they also open a window into who C.S. Lewis really was.

The Student

Clive Staples Lewis (“Jack” to his friends) was born on 29 November 1898 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, the second son of Albert Lewis, a promising attorney and his wife, Florence (“Flora”), daughter of an Anglican clergyman and one of the earliest female graduates (in Mathematics and Logic) from what is now Queen’s University, Belfast. She was probably the sharper of the parents, although “Jack” did not inherit her mathematical gifts. Were it not for a military service waiver from the Oxford University mathematics entrance examination hislife might have been very different.

Flora died of abdominal cancer in 1908. Lewis was a motherless son. Sent off to boarding school, his teenage years were generally miserable. Latterly he was privately tutored by his father’s former headmaster, the remarkable W.T.Kirkpatrick (known by “Jack” and his brother Warren as “The Great Knock”). Kirkpatrick had earlier abandoned aspirations to the Presbyterian ministry and was by this time an avowed atheist (yet, still with a decidedly Presbyterian work ethic!). His influence was substantial, both religiously (sadly) and intellectually. Lewis had probably completed the required reading for his Oxford Bachelor’s degree even before entering University College, Oxford. He sailed through his studies with “firsts” in classics, then in philosophy and history, and then in literature, and after some time he became a Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford.

The “Mere” Christian

Lewis tells the complex story of his pilgrimage to the Christian faith in genres ranging from the philosophical The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933) to the autobiographical Surprised by Joy (1955). Doubtless, elements of it are also reflected in his works of imagination — his “science-fiction,” his children’s books, and in The Great Divorce (1945).

Immersed in ancient, medieval, and modern literature Lewis was inevitably confronted by Christianity. He was helped by various other scholars like Neville Coghill (1899–1980, a Chaucer expert), J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973, already professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford), and Hugo Dyson (1896–1975), and he was influenced by writers like G.K. Chesterton and George MacDonald (whom he began to read as a teenager) — all of whom made a Christian profession.

Lewis came first to theism — and some time later to faith in Christ. Thereafter his thinking often expressed the common motif that the Christ-story was the ultimate story in which alone the longings and redemption-patterns in all great stories and myths were historically realized. Thus the need for the dying and rising divine figure would be echoed in as different literature as the ancient myths on the one hand to the Narnian Chronicles on the other.

In a sense (probably unwittingly), the Narnian Chronicles do in story form what Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) had done in dialogue form in Cur Deus Homo(Why God Became Man). Using what he called the “remoto Christo” principle (that is, without specific reference to the revelation of Christ in Scripture), he had attempted to show how the Gospel is necessary for our salvation.

Academic and Author

Lewis was an academic. An Oxford education was, and remains, one of the most rigorous and privileged in the world. While lectures are offered, the student is supervised by a tutor who is a scholar of distinction in his own right. Thus Lewis for many years listened to his students as they came weekly or fortnightly to “read” their papers to him. Many loved it — although not all: John Betjeman (1906–1984), later British Poet Laureate, was none-too-keen on Lewis. (He also failed to graduate.) Lewis, however, found it a trial. Being appointed to a professorship (an appointment of high distinction in the Oxford system) would have multiplied his salary and eased his tutorial work load. But the likelihood of this was probably in inverse proportion to the growth of his reputation as a popular Christian writer (the adjective “popular” being as damningas “Christian”).

Yet by any measure Lewis was an outstanding scholar. His best known academic works include a study of the literature of the Middle Ages, The Allegory of Love(1936), and his scintillating monograph on John Milton’s epic poem A Preface to Paradise Lost (1942). The eminence of his scholarship led to an invitation to write the volume on English Literature in the Sixteenth Century (1954) in the prestigious Oxford History of English Literature series. By the time of its publication, Oxford’s academic rival had claimed him, and in 1954 he became professor of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge, resigning only shortly before his death.

Companions on the Way

Any account of Lewis’ life would be incomplete without reference to a number of other influences, including (and especially) two women.

Chief among the influences on Lewis’ way of “doing” Christian theology was George MacDonald (1824–1905). In 1946 he published an anthology of MacDonald’s writings, noting that he had virtually never written on the Christian faith without reflecting his influence: “I know hardly any other writer who seems to be closer, or more continually close, to the Spirit of Christ Himself.” Certainly anyone who has read MacDonald’s fantasies such as Phantastes and Lilith will soon realize the source of many ideas that might otherwise be thought of as uniquely Lewisian. MacDonald, it should be noted, was deeply influenced by the world of Romanticism, and this impacted his view of the Gospel. Lewis on the other hand employed his imaginative genius in the cause of a more mainstream orthodox, if not consistently evangelical, Christianity.

Lewis’ name is virtually synonymous with the group of scholars and others who met regularly in Oxford in an informal literary brotherhood called (brilliantly) “The Inklings.” Here they would share one another’s work. It is remarkable that this little group included the authors both of The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings.

The two women whose lives were intertwined with Lewis’ were very different indeed. The first was Jane Moore, the mother of “Paddy” Moore, a young cadet with whom Lewis had trained for the army. They apparently promised to look after each other’s parent in the event of the other’s death. Moore was killed.

The relationship between Lewis and Mrs. Moore (which continued to her death in 1951) is one of the most enigmatic elements in the Lewis saga. Much has been made of it by both critical and sympathetic scholars. Was Jane Moore surrogate mother, sometime lover, or perhaps both? Whatever the truth, following his conversion, Lewis felt bound to provide support for her for the rest of her days, and he did this with an extraordinary sense of duty and single-mindedness.

In January 1950, Joy Davidman Gresham, an American writer, began corresponding with Lewis. Estranged (later divorced) from her husband, in 1952 she visited England with her two sons. Lewis enjoyed the challenge of her company, and in 1956 formally married her, thus enabling the Greshams to remain in England. In time, the relationship blossomed into love — which it may well already have been without Lewis clearly recognizing it. Joy died of cancer in 1960, and this led to Lewis publishing (originally under the nom-de-plume N.W.Clark) A Grief Observed (1961). After three years of mixed health, Lewis himself died on November 22, 1963.

The Lewis corpus has, of course, become a minor industry in its own right. His books have sold over 200 million copies. The Problem of Pain (1940), The Screwtape Letters (1942), Mere Christianity (1952, based on radio talks from 1941–1944), and The Four Loves (1960) have been particularly widely read, as have some of his sermons, notably “The Weight of Glory.” Perhaps more than any other twentieth-century author, C.S. Lewis has played a role in people’s understanding of the Christian faith akin to the one that hymns used to play. His strength lay in his use of the imagination rather than his expertise as either exegete or theologian. Interestingly, he himself found it somewhat tiresome to be paraded as the great popular apologist for the Christian faith.

The most widely-read Christian author of his time, Lewis left behind not only his many academic and popular works but also a substantial collection of correspondence and papers, which have guaranteed the continuation of the Lewis industry to the present day. It is an indication of his impact that while “the holidays” began for him, a vast plethora of articles, research theses, books, institutes, journals, fan clubs, documentaries and screenplays — not to mention movies — have now occupied a term that has lasted more than forty years.

This post was originally published by Tabletalk magazine in an issue dedicated to the life and significance of C.S. Lewis.

“Aslan and Jesus” Louis A. Markos with C.S. Lewis

Aslan

As an English professor, I have spent the last two decades guiding college students through the great books of the western intellectual tradition. And yet, though I have taught (and loved) the works of Homer, Sophocles, Virgil, Dante, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, and Dickens, I do not hesitate to assert that Aslan is one of the supreme characters in all of literature. Though many readers assume that Aslan, the lion king of Narnia who dies and rises again, is an allegory for Christ, Lewis himself disagreed.

According to his creator, Aslan is not an allegory for Christ but the Christ of Narnia. The distinction is vital. Were Aslan only an allegory, a mere stand-in for the hero of the gospels, he would not engage the reader as he does. In fact, as Lewis explained, Aslan is what the Second Person of the Trinity (God the Son) might have been like had he been incarnated in a magical world of talking animals and living trees. As such, Aslan takes on a force and a reality that speaks to us through the pages of the Chronicles of Narnia.

In Aslan, we experience all the mighty paradoxes of the Incarnate Son: he is powerful yet gentle, filled with righteous anger yet rich with compassion; he inspires awe and even terror (for he is not a tame lion), yet he is as beautiful as he is good; The modern world has ripped apart the Old and New Testament, leaving us with two seemingly irreconcilable deities:

an angry, wrathful Yahweh who cannot be approached, and a meek and mild Jesus who is too timid to defend his followers from evil. Aslan allows us to reintegrate—not just intellectually and theologically, but emotionally and viscerally as well—the two sides of the Triune God who calls out to us on every page of the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation.

Every time a character comes into the presence of Aslan, he learns, to his great surprise, that something can be both terrible and beautiful, that it can provoke, simultaneously, feelings of fear and joy. Borrowing a word from Rudolph Otto, Lewis referred to this dual feeling as the numinous. The numinous is what Isaiah and John felt when they were carried, trembling and awe-struck, into the throne room of God, and heard the four-faced cherubim cry out “holy, holy, holy!” It is what Moses felt as he stood before the Burning Bush, or Jacob when he wrestled all night with God, or Job when Jehovah spoke to him from the whirlwind, or David when he was convicted of his sin with Bathsheba and experienced (all at once) the wrathful judgment and infinite mercy of the Holy One of Israel.

Our age has lost its sense of the numinous, for it has lost its sense of the sacred. Through the character of Aslan, Lewis not only instructs us in the nature of the numinous, but trains us how to react when we are in its presence. When we finish the Chronicles, we may not be able to define the numinous, but we know we have felt it: each and every time Aslan appears on the page.

Jesus

No person has ever had a greater impact on the history of the world, and yet no person has been the focal point of more controversy and strife. No person has ever been worshipped with such devotion or manipulated with such selfish ingenuity. For well over a century, an ever-changing band of biblical “scholars” (some of them genuine, but most of them self-appointed) have organized themselves under the rubric of the Jesus Seminar and have taken as their goal the grail-like search for the “historical Jesus.” Sadly, though the majority of their findings are based on their readings of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (with an occasional gnostic gospel thrown in),

most members of the Jesus Seminar refuse to treat the canonical gospels with the respect they deserve. And that despite the growing number of historians and textual critics who have judged the gospels to be reliable historical documents based on eyewitness accounts that corroborate, rather than duplicate, one another.

Though C. S. Lewis was not a trained biblical scholar, he was an expert reader of literature with a fine eye for the distinctions between genres. Long before modern scholarship confirmed the historical accuracy of the gospels, Lewis had already explained to his readers that the Jesus of the gospels and the “historical Jesus” of revisionist scholarship were one and the same.

Anyone who reads the gospels alongside other ancient texts will immediately see the difference. There is nothing legendary about the gospels. They are, Lewis asserts, sober biographies grounded in real, down-to-earth details— the kind of details that do not appear in literature until the 19th century. As for Jesus himself, he emerges from the gospels with a concrete

As for Jesus himself, he emerges from the gospels with a concrete reality that surpasses all other figures in the ancient world (only Socrates comes close). When we read the gospels, we know Jesus in a way we do not know anyone else before the modern period.

As for the claims Jesus makes in the gospels, Lewis, in what is perhaps his best known apologetical argument, defuses all those critics who would treat Jesus as a good teacher or prophet and nothing more. In Mere Christianity (II. 3), Lewis gives the lie to this attempt to domesticate and defang the historical Jesus of the gospels.

Again and again, Lewis reminds us, Jesus makes incredible claims about himself: he is the Way, the Truth and the Life; he is the Resurrection and the Life; he is one with the Father; he has the authority to forgive sins; he calls on people to follow him (and not just his teachings); he takes upon himself the power to reinterpret the Law.

A person who made these claims and was not the Son of God would not be a prophet or even a good man. He would either be a deceiver on a grand scale or a certifiable maniac. Yet the overwhelming consensus of the gospels and of those who knew Jesus rule out the possibility that he was either a liar or a lunatic. Once these two options are eliminated, however, we are left with only one possibility: that he was who he claimed to be.

And that is why Lewis concludes that we can shut Jesus up as a lunatic, kill him as a devil, or fall at his feet in worship—but “let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about His being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

Articles adapted from Markos, Louis A. (2012-10-01). A To Z With C. S. Lewis (Kindle Locations 74-79 & 377-379). . Kindle Edition.

Is It Wrong to Want Heaven Now? By C.S. Lewis

We are very shy nowadays of even mentioning heaven. We are afraid of the jeer about ‘pie in the sky’, and of being told that we are trying to ‘escape’ from the duty of making a happy world here and now into dreams of a happy world elsewhere. But either there is ‘pie in the sky’ or there is not. If there is not, then Christianity is false, for this doctrine is woven into its whole fabric. If there is, then this truth, like any other, must be faced, whether it is useful at political meetings or no. Again, we are afraid that heaven is a bribe, and that if we make it our goal we shall no longer be disinterested. It is not so. Heaven offers nothing that a mercenary soul can desire. It is safe to tell the pure in heart that they shall see God, for only the pure in heart want to. There are rewards that do not sully motives. A man’s love for a woman is not mercenary because he wants to marry her, nor his love for poetry mercenary because he wants to read it, nor his love of exercise less disinterested because he wants to run and leap and walk. Love, by definition, seeks to enjoy its object.

(Lewis, C. S. A Year with C. S. Lewis (p. 357). Harper Collins, Inc., excerpted from The Problem of Pain).

Aim At Heaven

Hope is one of the Theological virtues. This means that a continual looking forward to the eternal world is not (as some modern people think) a form of escapism or wishful thinking, but one of the things a Christian is meant to do. It does not mean that we are to leave the present world as it is. If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were just those who thought most of the next. The Apostles themselves, who set on foot the conversion of the Roman Empire, the great men who built up the Middle Ages, the English Evangelicals who abolished the Slave Trade, all left their mark on Earth, precisely because their minds were occupied with Heaven. It is since Christians have largely ceased to think of the other world that they have become so ineffective in this. Aim at Heaven and you will get earth ‘thrown in’: aim at earth and you will get neither. It seems a strange rule, but something like it can be seen at work in other matters. Health is a great blessing, but the moment you make health one of your main, direct objects you start becoming a crank and imagining there is something wrong with you. You are only likely to get health provided you want other things more—food, games, work, fun, open air. In the same way, we shall never save civilisation as long as civilisation is our main object. We must learn to want something else even more.

Lewis, C. S. (2009-03-17). A Year with C. S. Lewis (p. 358). Harper Collins, Inc., excerpted from Mere Christianity).

C.S. Lewis Contrasting Heaven and Hell

“Of Heaven and Earth”

“I believe, to be sure, that any man who reaches Heaven will find that what he abandoned (even in plucking out his right eye) has not been lost: that the kernel of what he was really seeking even in his most depraved wishes will be there, beyond expectation, waiting for him in ‘the High Countries’. In that sense it will be true for those who have completed the journey (and for no others) to say that good is everything and Heaven everywhere. But we, at this end of the road, must not try to anticipate that retrospective vision. If we do, we are likely to embrace the false and disastrous converse and fancy that everything is good and everywhere is Heaven. But what, you ask, of earth? Earth, I think, will not be found by anyone to be in the end a very distinct place. I think earth, if chosen instead of Heaven, will turn out to have been, all along, only a region in Hell: and earth, if put second to Heaven, to have been from the beginning a part of Heaven itself.” —from The Great Divorce, Preface

C.S. Lewis. A Year with C. S. Lewis (p. 348). Harper Collins, Inc.. Kindle Edition.