(The interview below is “heady” stuff – but very important. There is a huge movement of “scientism” in our culture that denies the reality and existence of the soul. One of my favorite teachers when I was at Talbot School of Theology was Dr. J.P. Moreland. What I love about Moreland is that he is a deep thinker and yet he has the ability to explain complex truths in a way that lay people can understand. Like anything Moreland writes or says, this interview will be challenging, enlightening, and clarifying – I hope that you will be able to better understand the reality of the soul and the overwhelming evidence for the existence of God as you read this interview with former atheist – turned Christian – Lee Strobel. Reading this article will exercise your mind and bring joy to your soul, and will be well worth your serious attention – enjoy! David P. Craig)

The Evidence of Consciousness: The Enigma of the Mind

When I pulled up to J. P. Moreland’s house on a cool and foggy morning, he was outside with a cup of coffee in his hand, having just walked home from a chat with some neighbors. His graying hair was close-cropped, his mustache neatly trimmed, and he was looking natty in a red tie, blue shirt, and dark slacks. “Good to see you again,” he said as we shook hands. “Come on in.” We walked into his living room, where he settled into a floral-patterned chair and I eased into an adjacent couch. The setting was familiar to me, since I had previously interviewed him on other challenging topics for The Case for Christ and The Case for Faith (See: “The Circumstantial Evidence” in: Lee Strobel, The Case for Christ, 244–57, and “Objection #6: A Loving God Would Never Torture People in Hell,” in: Lee Strobel, The Case for Faith, 169–94).

Both times I found him to have an uncanny ability to discuss abstract issues and technical matters in understandable but accurate language. That’s unusual for a scientist, uncommon for a theologian, and downright rare for a philosopher! Moreland’s science training came at the University of Missouri, where he received a degree in chemistry. He was subsequently awarded the top fellowship for a doctorate in nuclear chemistry at the University of Colorado but declined the honor to pursue a different career path. He then earned a master’s degree in theology at Dallas Theological Seminary and a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Southern California. Moreland developed an early interest in issues relating to human consciousness, returning to that theme time after time in his various books. He has written, edited, or coauthored Christianity and the Nature of Science, Body and Soul, The Life and Death Debate, Beyond Death, Does God Exist? Christian Perspectives on Being Human, The Creation Hypothesis, Scaling the Secular City, Love Your God with All Your Mind, Naturalism: A Critical Analysis, and many other books.

Also, he has authored more than fifty technical articles for Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, American Philosophical Quarterly, Journal of Psychology and Theology, Metaphilosophy, and a host of other journals. Moreland’s memberships include national scientific, philosophical, and theological societies. Currently, he’s a professor in the highly respected philosophy program at the Talbot School of Theology, where he teaches on numerous topics, including philosophy of mind. As we began our interview, I thought it would be a good idea to get straight on some key definitions—something that’s not always easy when discussing consciousness.

REGAINING CONSCIOUSNESS

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once said it may be difficult to define pornography, “but I know it when I see it” (Justice Potter Stewart [concurring], Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 198,1964). Similarly, consciousness can be a challenging concept to describe, even though our own conscious thoughts are quite tangible to ourselves. As J. R. Smythies of the University of Edinburgh put it: “The consciousness of other people may be for me an abstraction, but my own consciousness is for me a reality” (J. R. Smythies, “Some Aspects of Consciousness,” in Arthur Koestler and J. R. Smythies, editors, Beyond Reductionism. London: Hutchinson, 1969, 235, quoted in Arthur C. Custance, The Mysterious Matter of Mind, 35).

“What is consciousness?” Moreland said, echoing the opening question that I had just posed to him. “Well, a simple definition is that consciousness is what you’re aware of when you introspect. When you pay attention to what’s going on inside of you, that’s consciousness.” He looked at me and apparently could see from my expression that I needed a fuller description. “Think of it like this,” he continued. “Suppose you were having an operation on your leg, and suddenly you begin to be aware of people talking about you. Someone says, ‘I think he’s recovering.’ You start to feel an ache in your knee. You say to yourself, ‘Where am I? What’s going on?’ And you start to remember you were operated on. What you’re doing is regaining consciousness. In short, consciousness consists of sensations, thoughts, emotions, desires, beliefs, and free choices that make us alive and aware.”

“What if consciousness didn’t exist in the world?” I asked. “I’ll give you an example,” Moreland replied. “Apples would still be red, but there would be no awareness of red or any sensations of red.” “What about the soul?” I asked. “How would you define that?” “The soul is the ego, the ‘I,’ or the self, and it contains our consciousness. It also animates our body. That’s why when the soul leaves the body, the body becomes a corpse. The soul is immaterial and distinct from the body.” “At least,” I observed, “that’s what the Bible teaches.” “Yes, Christians have understood this for twenty centuries,” he said. “For example, when Jesus was on the cross, he told the thief being crucified next to him that he would be with Jesus immediately after his death and before the final resurrection of his body (Luke 23:43: “Today you will be with me in paradise”).

Jesus described the body and soul as being separate entities when he said, ‘Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul’ (Matthew 10:28). The apostle Paul says that “to be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8).

I was curious about whether belief in the soul is a universal phenomenon. “What about beyond Christianity?” I asked. “Is this concept present in other cultures as well?” “We know that dualism was taught by the ancient Greeks, although, unlike Christians, they believed the body and soul were alien toward each other,” he explained. “In contemporary terms, I’d agree with physicalist Jaegwon Kim, who acknowledged that ‘something like this dualism of personhood, I believe, is common lore shared across most cultures and religious traditions’” (Jaegwon Kim, “Lonely Souls: Causality and Substance Dualism,” in Kevin Corcoran, editor, Soul, Body, and Survival. Ithica, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 2001).

Still, there are those who deny dualism and instead believe we are solely physical beings who are, as geneticist Francis Crick said, “no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules” (Francis Crick, The Astonishing Hypothesis. New York: Scribner’s, 1994, 3). To explore this issue, I decided to take an unusual approach in my interview with Moreland by asking him to imagine—for just a few minutes—that these physicalists are right.

WHAT IF PHYSICALISM IS TRUE?

“Let’s face it,” I said, “some people flatly deny that we have an immaterial soul. John Searle said, ‘In my worldview, consciousness is caused by brain processes’ (“What Is Consciousness?” in Closer to Truth). In other words, they believe consciousness is purely a product of biology. As brain scientist Barry Beyerstein said, just as the kidneys produce urine, the brain produces consciousness” (“Do Brains Make Minds?” on Closer to Truth).

Moreland was listening carefully as I spoke, his head slightly cocked. I continued by saying, “Do me a favor, J. P. —assume for a moment that the physicalists are right. What are the logical implications if physicalism is true?” His eyes widened. “Oh, there would be several key ones,” he replied.

“Give me three,” I said. Moreland was more than willing. “First, if physicalism is true, then consciousness doesn’t really exist, because there would be no such thing as conscious states that must be described from a first-person point of view,” he said. “You see, if everything were matter, then you could capture the entire universe on a graph—you could locate each star, the moon, every mountain, Lee Strobel’s brain, Lee Strobel’s kidneys, and so forth. That’s because if everything is physical, it could be described entirely from a third-person point of view. And yet we know that we have first-person, subjective points of view—so physicalism can’t be true.” Clearly, Moreland was warming up to this exercise.

“The second implication,” he continued, “is that there would be no free will. That’s because matter is completely governed by the laws of nature. Take any physical object,” he said as he glanced out the window, where the fog was breaking up. “For instance, a cloud,” he said. “It’s just a material object, and its movement is completely governed by the laws of air pressure, wind movement, and the like. So if I’m a material object, all of the things I do are fixed by my environment, my genetics, and so forth. “That would mean I’m not really free to make choices. Whatever’s going to happen is already rigged by my makeup and environment. So how could you hold me responsible for my behavior if I wasn’t free to choose how I would act? This is one of the reasons we lost the Vietnam War.” I was following him until that last statement, which seemed oddly incongruous to me. “What has this got to do with Vietnam?” I asked. Moreland explained: “I heard a former advisor to the president say that B. F. Skinner’s behaviorism influenced the Pentagon’s strategy. Skinner believed that we’re just physical objects, so you can condition people, just like you can condition a laboratory animal by applying electric shocks. Keep doing certain things over and over, and you can change behavior. So in Vietnam, we bombed, we came back, we bombed, we came back, we bombed, and so forth. We assumed that after we gave the North Vietnamese shock after shock, pretty soon we could manipulate their behavior. After all, they’re just physical objects responding to stimuli. Eventually they had to give in.” “But they didn’t,” I said. “That’s right. It didn’t work.” “Why?” “Because there was more to the Vietnamese than their physical brains responding to stimuli. They have souls, desires, feelings, and beliefs, and they could make free choices to suffer and to stand firm for their convictions despite our attempt to condition them by our bombing.

“So if the materialists are right, kiss free will good-bye. In their view, we’re just very complicated computers that behave according to the laws of nature and the programming we receive. But, Lee, obviously they’re wrong—we do have free will. We all know that deep down inside. We’re more than just a physical brain.

“Third, if physicalism were true, there would be no disembodied intermediate state. According to Christianity, when we die, our souls leave our bodies and await the later resurrection of our bodies from the dead. We don’t cease to exist when we die. Our souls are living on. “This happens in near-death experiences. People are clinically dead, but sometimes they have a vantage point from above, where they look down at the operating table that their body is on. Sometimes they gain information they couldn’t have known if this were just an illusion happening in their brain. One woman died and she saw a tennis shoe that was on the roof of the hospital. How could she have known this? “If I am just my brain, then existing outside the body is utterly impossible. When people hear of near-death experiences, they don’t think that if they looked up at the hospital ceiling, they’d see a pulsating brain with a couple of eyeballs dangling down, right? When people hear near-death stories, Lee, they are intuitively attributing to that person a soul that could leave the body. And clearly these stories make sense, even if we’re not sure they’re true. We’ve got to be more than our bodies or else these stories would be ludicrous to us.” Moreland seemed to be sidestepping this issue a bit. “How about you personally?” I asked. “Do you think near-death experiences are true?” “We have to be careful with the data and not overstate things, but I do think they provide at least a minimalist case for consciousness surviving death,” he said. “In fact, as far back as 1965, psychologist John Beloff wrote in The Humanist that the evidence of near-death experiences already indicates ‘a dualistic world where mind or spirit has an existence separate from the world of material things.’ He conceded that this could ‘present a challenge to humanism as profound in its own way as that which Darwinian evolution did to Christianity a century ago.’ ” (Cited in David Winter, Hereafter: What Happens after Death? Wheaton, Ill.: Harold Shaw, 1972, 33–34).

Moreland paused before adding one other comment. “Regardless of what anyone thinks about near-death experiences, we do have confirmation that Jesus was put to death and was later seen alive by credible eyewitnesses,” he said. “Not only does this provide powerful historical corroboration that it’s possible to survive after the death of our physical body, but it also gives Jesus great credibility when he teaches that we have both a body and an immaterial spirit” (For a short description of the evidence for the Resurrection, see Gary R. Habermas and J. P. Moreland, Beyond Death, 111–54).

THE INNER AND PRIVATE MIND

At this point, having considered Moreland’s critique of physicalism, I wanted to hear his affirmative case that consciousness and the soul are immaterial entities. “What positive evidence is there that consciousness and the self are not merely a physical process of the brain?” I asked. “We have experimental data, for one thing,” he replied. “For example, neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield electrically stimulated the brains of epilepsy patients and found he could cause them to move their arms or legs, turn their heads or eyes, talk, or swallow. Invariably the patient would respond by saying, ‘I didn’t do that. You did.’ (See: Wilder Penfield, The Mystery of the Mind, 76–77).

According to Penfield, ‘the patient thinks of himself as having an existence separate from his body.’ (Wilder Penfield, “Control of the Mind” Symposium at the University of California Medical Center, San Francisco, 1961, quoted in Arthur Koestler, Ghost in the Machine. London: Hutchinson, 1967, 203).

“No matter how much Penfield probed the cerebral cortex, he said, ‘There is no place . . . where electrical stimulation will cause a patient to believe or to decide.’ (Wilder Penfield, The Mystery of the Mind, 77–78).

That’s because those functions originate in the conscious self, not the brain. “A lot of subsequent research has validated this. When Roger Sperry and his team studied the differences between the brain’s right and left hemispheres, they discovered the mind has a causal power independent of the brain’s activities. This led Sperry to conclude materialism was false (See: Roger W. Sperry, “Changed Concepts of Brain and Consciousness: Some Value Implications,” Zygon, March 1985).

“Another study showed a delay between the time an electric shock was applied to the skin, its reaching the cerebral cortex, and the self-conscious perception of it by the person (Laurence W. Wood, “Recent Brain Research and the Mind-Body Dilemma,” The Asbury Theological Journal, vol. 41, no. 1,1986). This suggests the self is more than just a machine that reacts to stimuli as it receives them. In fact, the data from various research projects are so remarkable that Laurence C. Wood said, ‘many brain scientists have been compelled to postulate the existence of an immaterial mind, even though they may not embrace a belief in an after-life.’””(Ibid).

“What about beyond the laboratory?” I asked. “There are valid philosophical arguments as well,” he said. “For instance, I know that consciousness isn’t a physical phenomenon because there are things that are true of my consciousness that aren’t true of anything physical.” “For instance . . . ,” I said, prompting him further. “For example, some of my thoughts have the attribute of being true. Tragically, some of my thoughts have the attribute of being false—like the Chicago Bears are going to go to the Super Bowl,” he said with a chuckle. “However, none of my brain states are true or false. No scientist can look at the state of my brain and say, ‘Oh, that particular brain state is true and that one’s false.’ So there’s something true of my conscious states that are not true of any of my brain states, and consequently they can’t be the same thing. “Nothing in my brain is about anything. You can’t open up my head and say, ‘You see this electrical pattern in the left hemisphere of J. P. Moreland’s brain? That’s about the Bears.’ Your brain states aren’t about anything, but some of my mental states are. So they’re different.

“Furthermore, my consciousness is inner and private to me. By simply introspecting, I have a way of knowing about what’s happening in my mind that is not available to you, my doctor, or a neuroscientist. A scientist could know more about what’s happening in my brain than I do, but he couldn’t know more about what’s happening in my mind than I do. He has to ask me.” When I asked Moreland for an illustration of this, he said, “Have you heard of Rapid Eye Movement?” “Sure,” I replied. “What does it indicate?” “Dreaming.” “Exactly. How do scientists know that when there is a certain eye movement that people are dreaming? They’ve had to wake people and ask them. Scientists could watch the eyes move and read a printout of what was physically happening in the brain, so they could correlate brain states with eye movements. But they didn’t know what was happening in the mind. Why? Because that’s inner and private. “So the scientist can know about the brain by studying it, but he can’t know about the mind without asking the person to reveal it, because conscious states have the feature of being inner and private, but the brain’s states don’t.”

THE REALITY OF THE SOUL

For centuries, the human soul has enchanted poets, intrigued theologians, challenged philosophers, and dumbfounded scientists. Mystics, like Teresa of Åvila in the sixteenth century, have described it eloquently: “I began to think of the soul as if it were a castle made of a single diamond or of very clear crystal, in which there are many rooms, just as in heaven there are many mansions” (Mark Water, compiler, The New Encyclopedia of Christian Quotations.Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 2000), 972. Teresa’s reference to mansions is an allusion to John 14:2).

Moreland was understandably more precise in analyzing the soul, though unfortunately less poetic. He had already clarified that the soul contains our consciousness. Still, he hadn’t offered any reason to believe that the soul is an actual entity. It was time, I felt, to press him on this

issue. “What makes you think that the soul is real?” I asked.

Moreland replied by saying, “First, we’re aware that we’re different from our consciousness and our body. We know that we’re beings who have consciousness and a body, but we’re not merely the same thing as our conscious life or our physical life. “Let me give you an illustration of how we’re not the same thing as our personality traits, our memories, and our consciousness. I had a student a few years ago whose sister had a terrible accident on her honeymoon. She was knocked unconscious and lost all of her memories and a good bit of her personality. She did not believe she had been married. As she began to recover, they showed her videos of the wedding to convince her that she had actually married her husband. She eventually got to the point where she believed it, and she got remarried to him.

“Now, we all knew this was the same person all along.” This was Jamie’s sister. She was not a different person, though she was behaving differently. But she had totally different memories. She had lost her old memories and she didn’t even have the same personality. What that proves is you can be the same person even if you lose old memories and gain new memories, or you lose some of your old personality traits and gain new personality traits. “Now, if I were just my consciousness, when my consciousness was different, I’d be a different person. But we know that I can be the same person even though my consciousness changes, so I can’t be the same thing as my consciousness. I’ve got to be the ‘self,’ or soul, that contains my consciousness.

“Same with my body. I can’t be the same thing as my body or brain. There was a story on television about an epileptic who underwent an operation in which surgeons removed fifty-three percent of her brain. When she woke up, nobody said, ‘We have forty-seven percent of a person here.’ A person can’t be divided into pieces. You are either a person or you’re not. But your brain and your body can be divided. So that means I can’t be the same thing as my body.”

Those illustrations helped, though I said, “The fact that the soul and consciousness are invisible makes it difficult to conceptualize them.” “Sure, that’s true,” he replied. “My soul and my consciousness are invisible, though my body is visible. That’s another distinction. In fact, I remember the time when my daughter was in the fifth grade and we were having family prayers. She said, ‘Dad, if I could see God, it would help me believe in him.’ I said, ‘Well, honey, the problem isn’t that you’ve never seen God. The problem is that you’ve never seen your mother.’ And her mother was sitting right next to her! “My daughter said, ‘What do you mean, Dad?’ I said, ‘Suppose without hurting your mom, we were able to take her apart cell by cell and peek

inside each one of them. We would never come to a moment where we would say, ‘Look—here’s what Mommy’s thinking about doing the rest of the day.’ Or ‘Hey, this cell contains Mommy’s feelings.’ Or ‘So this is what Mom believes about pro football.’ We couldn’t find Mommy’s thoughts, beliefs, desires, or her feelings. “‘Guess what else we would never find? We’d never find Mommy’s ego or her self. We would never say, ‘Finally, in this particular brain cell, there’s Mommy. There’s her ego, or self.’ That’s because Mommy is a person, and persons are invisible. Mommy’s ego and her conscious life are invisible. Now, she’s small enough to have a body, while God is too big to have a body—so let’s pray!’ “The point is this, Lee: I am a soul, and I have a body. We don’t learn about people by studying their bodies. We learn about people by finding out how they feel, what they think, what they’re passionate about, what their worldview is, and so forth. Staring at their body might tell us whether they like exercise, but that’s not very helpful. That’s why we want to get ‘inside’ people to learn about them. “So my conclusion is that there’s more to me than my conscious life and my body. In fact, I am a ‘self,’ or an ‘I,’ that cannot be seen or touched unless I manifest myself through my behavior or my talk. I have free will because I’m a ‘self,’ or a soul, and I’m not just a brain.”

OF COMPUTERS AND BATS

Moreland’s denial that the brain produces consciousness made me think of the debate over whether future computers can become sentient. I decided to ask him to weigh in on the issue—although his ultimate conclusion was never in doubt. “If a machine can achieve equal or greater brain power as human beings, then some physicalists say the computer would become conscious,” I said. “I assume you would disagree with that.” Moreland chuckled. “One atheist said that when computers reach the point of imitating human behavior, only a racist would deny them full human rights. But of course that’s absurd.

Nobel-winner John Eccles said he’s ‘appalled by the naiveté’ of those who foresee computer sentience. He said there’s ‘no evidence whatsoever for the statement made that, at an adequate level of complexity, computers also would achieve self-consciousness’ (Quoted in Robert W. Augros and George N. Stanciu, The New Story of Science, 170).

“Look, we have to remember that computers have artificial intelligence, not intelligence. And there’s a huge difference. There’s no ‘what it’s like to be a computer.’ A computer has no ‘insides,’ no awareness, no first-person point of view, no insights into problems. A computer doesn’t think, ‘You know what? I now see what this multiplication problem is really like.’ A computer can engage in behavior if it’s wired properly, but you’ve got to remember that consciousness is not the same as behavior. Consciousness is being alive; it’s what causes behavior in really conscious beings. But what causes behavior in a computer is electric circuitry.

“Let me illustrate my point. Suppose we had a computerized bat that we knew absolutely everything about from a physical point of view. We would have exhaustive knowledge of all its circuitry so that we could predict everything this bat would do when it was released into the environment. “Contrast that with a real bat. Suppose we knew everything about the organs inside the bat—its blood system, nervous system, brain, heart, lungs. And suppose that we could predict everything this bat would do when released into the environment. There would still be one thing that we would have no idea about: what it’s like to be a bat. What it’s like to hear, to feel, to experience sound and color. That stuff involves the ‘insides’ of the bat, its point of view. That’s the difference between a conscious, sentient bat and a computerized bat. “So in general, computers might be able to imitate intelligence, but they won’t ever have consciousness. We can’t confuse behavior with what it’s like to be alive, awake, and sentient. A future superintelligent computer might be programmed to say it’s conscious or even behave as if it were conscious, but it can never truly become conscious, because consciousness is an immaterial entity apart from the brain.” Moreland’s choice of a bat for his illustration was an oblique reference to New York University philosopher Thomas Nagel’s famous 1974 essay “What Is it Like to Be a Bat?” (See: Thomas Nagel, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” Philosophical Review 83, October, 1974).

Thinking about life from a bat’s perspective prompted me to briefly pursue another line of inquiry on a tangential topic. “What about animals—do they have souls or consciousness?” I asked. “Absolutely,” came his quick answer. “In several places the Bible uses the word ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’ when discussing animals. For example:

Genesis 1:30, “And to every beast of the earth and to every bird of the heavens and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food.” And it was so.”

Leviticus 24:18, “Whoever takes an animal’s life shall make it good, life for life.”

Ecclesiastes 3:19, “For what happens to the children of man and what happens to the beasts is the same; as one dies, so dies the other. They all have the same breath, and man has no advantage over the beasts, for all is vanity.”

Revelation 8:9, “A third of the living creatures in the sea died, and a third of the ships were destroyed.”

Animals are not simply machines. They have consciousness and points of view. But the animal soul is much simpler than the human soul. For example, the human soul is capable of free moral action, but I think the animal soul is determined. Also, Augustine said animals have thoughts, but they don’t think about their thinking. And while we have beliefs about our beliefs, animals don’t. “You see, the human soul is vastly more complicated because it’s made in the image of God. So we have self-reflection and self-thinking. And while the human soul survives the death of its body, I don’t think the animal soul outlives its body. I could be wrong, but I think the animal soul ceases to exist at death.” Bad news, it seems, for the bat.

CONSCIOUSNESS AND EVOLUTION

Moreland had made a cogent case for consciousness and the soul being independent of our brain and body. “How does this present a problem for Darwinists?” I asked. Moreland glanced down at some notes he had brought along. “As philosopher Geoffrey Medell said, ‘The emergence of consciousness, then, is a mystery, and one to which materialism fails to provide an answer.’ Atheist Colin McGinn agrees. He asks, ‘How can mere matter originate consciousness? How did evolution convert the water of biological tissue into the wine of consciousness? Consciousness seems like a radical novelty in the universe, not prefigured by the aftereffects of the Big Bang. So how did it contrive to spring into being from what preceded it?’ ”

Moreland looked squarely at me. “Here’s the point: you can’t get something from nothing,” he declared. “It’s as simple as that. If there were no God, then the history of the entire universe, up until the appearance of living creatures, would be a history of dead matter with no consciousness. You would not have any thoughts, beliefs, feelings, sensations, free actions, choices, or purposes. There would be simply one physical event after another physical event, behaving according to the laws of physics and chemistry.”

Moreland stopped for a moment to make sure this picture was vivid in my mind. Then he leaned forward and asked pointedly: “How, then, do you get something totally different—conscious, living, thinking, feeling, believing creatures—from materials that don’t have that? That’s getting something from nothing! And that’s the main problem. “If you apply a physical process to physical matter, you’re going to get a different arrangement of physical materials. For example, if you apply the physical process of heating to a bowl of water, you’re going to get a new product—steam—which is just a more complicated form of water, but it’s still physical. And if the history of the universe is just a story of physical processes being applied to physical materials, you’d end up with increasingly complicated arrangements of physical materials, but you’re not going to get something that’s completely nonphysical. That is a jump of a totally different kind. “At the end of the day, as Phillip Johnson put it, you either have ‘In the beginning were the particles,’ or ‘In the beginning was the Logos,’ which means ‘divine mind.’ If you start with particles, and the history of the universe is just a story about the rearrangement of particles, you may end up with a more complicated arrangement of particles, but you’re still going to have particles. You’re not going to have minds or consciousness.

“However—and this is really important—if you begin with an infinite mind, then you can explain how finite minds could come into existence. That makes sense. What doesn’t make sense—and which many atheistic evolutionists are conceding—is the idea of getting a mind to squirt into existence by starting with brute, dead, mindless matter. That’s why some of them are trying to get rid of consciousness by saying it’s not real and that we’re just computers.” He smiled after that last statement, then added: “However, that’s a pretty difficult position to maintain while you’re conscious!”

THE EMERGENCE OF THE MIND

“Still,” I protested, “some scientists maintain that consciousness is just something that happens as a natural byproduct of our brain’s complexity. They believe that once evolution gave us sufficient brain capacity, consciousness inexorably emerges as a biological process.”

“Let me mention four problems with that,” Moreland insisted. “First, they are no longer treating matter as atheists and naturalists treat matter—namely, as brute stuff that can be completely described by the laws of chemistry and physics. Now they’re attributing spooky, soulish, or mental potentials to matter.” “What do you mean by ‘potentials’?” “They’re saying that prior to this level of complexity, matter contained the potential for mind to emerge—and at the right moment, guess what happened? These potentials were activated and consciousness was sparked into existence.” “What’s wrong with that theory?” “That is no longer naturalism,” he said. “That’s panpsychism.” That was a new term to me. “Pan what?” “Panpsychism,” he repeated. “It’s the view that matter is not just inert physical stuff, but that it also contains proto-mental states in it. Suddenly, they’ve abandoned a strict scientific view of matter and adopted a view that’s closer to theism than to atheism. Now they’re saying that the world began not just with matter, but with stuff that’s mental and physical at the same time. Yet they can’t explain where these pre-emergent mental properties came from in the first place. And this also makes it hard for them to argue against the emergence of God.”

“The emergence of God?” I asked. “What do you mean by that?” “If a finite mind can emerge when matter reaches a certain level of complexity, why couldn’t a far greater mind—God—emerge when millions of brain states reach a greater level of consciousness? You see, they want to stop the process where they want it to stop—at themselves—but you can’t logically draw that line. How can they know that a very large God hasn’t emerged from matter, because, after all, haven’t a lot of people had religious experiences with God?” “That wouldn’t be the God of Christianity,” I pointed out. “Granted,” he replied. “But this is still a problem for atheists.

And there’s a second problem: they would still be stuck with determinism, because if consciousness is just a function of the brain, then I’m my brain, and my brain functions according to the laws of chemistry and physics. To them, the mind is to the brain as smoke is to fire. Fire causes smoke, but smoke doesn’t cause anything. It’s just a byproduct. Thus, they’re locked into determinism.

“Third, if mind emerged from matter without the direction of a superior Intelligence, why should we trust anything from the mind as being rational or true, especially in the area of theoretical thinking? “Let me give you an analogy. Let’s say you had a computer that was programmed by random forces or by nonrational laws without a mind being behind it. Would you trust a printout from that machine? Of course not. Well, same with the mind—and that’s a problem for Darwinists. And by the way, you can’t use evolution as an explanation for why the mind should be considered trustworthy, because theoretical thinking does not contribute to survival value.”

Moreland’s comments reminded me of the famous quote from British evolutionist J. B. S. Haldane: “If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of the atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true . . . and hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms” (J. B. S. Haldane, “When I am Dead,” in Possible Worlds and Other Essays. London: Chatto and Winduw, 1927, 209, quoted in C. S. Lewis, Miracles. London: Fontana, 1947, 19).

“Here’s the fourth problem,” Moreland went on, “If my mind were just a function of the brain, there would be no unified self. Remember, brain function is spread throughout the brain, so if you cut the brain in half, like the girl who lost fifty-three percent of her brain, then some of that function is lost. Now you’ve got forty-seven percent of a person. Well, nobody believes that. We all know she’s a unified self, because we all know her consciousness and soul are separate entities from her brain.

“There’s one other aspect of this, called the ‘binding problem.’ When you look around the room, you see many things at the same time,” he said, gesturing around at various objects in our field of vision. “You see a table, a couch, a wall, a painting in a frame. Every individual thing has light waves bouncing off of it and they’re striking a different location in your eyeball and sparking electrical activity in a different region of the brain. That means there is no single part of the brain that is activated by all of these experiences. Consequently, if I were simply my physical brain, I would be a crowd of different parts, each having its own awareness of a different piece of my visual field. “But that’s not what happens. I’m a unified ‘I’ that has all of these experiences at the same time. There is something that binds all of these experiences and unifies them into the experience of oneself—me—even though there is no region of the brain that has all these activation sites. That’s because my consciousness and my ‘self’ are separate entities from the brain.”

Moreland was on a roll, but I jumped in anyway. “What about recent brain studies that have shown activity in certain areas of the brain during meditation and prayer?” I asked. “Don’t those demonstrate that there’s a physical basis for these religious experiences, as opposed to an immaterial basis through the soul?” “No, it doesn’t. All it shows is a physical correlation with religious experiences,” he replied. “You’ll have to explain that,” I said. “Well, there’s no question that when I’m praying, smelling a rose, or thinking about something, my brain still exists. It doesn’t pop out of existence when I’m having a conscious life, including prayer. And I would be perfectly happy if scientists were to measure what was going on in my brain while I’m praying, feeling forgiveness, or even thinking about lunch. But remember: just because there is a correlation between two things, that doesn’t mean they’re the same thing. Just because there’s a correlation between fire and smoke, this doesn’t mean smoke is the same as fire.

“Now, sometimes your brain states can cause your conscious states. For example, if you lose brain functioning due to Alzheimer’s disease, or you get hit over the head, you lose some of your mental conscious life. But there’s also evidence that this goes the other way as well. There are data showing that your conscious life can actually reconfigure your brain. “For example, scientists have done studies of the brains of people who worried a lot, and they found that this mental state of worry changed their brain chemistry. They’ve done studies of the brain patterns of little children who were not nurtured and loved, and their patterns are different than children who have warm experiences of love and nurture. So it’s not just the brain that causes things to happen in our conscious life; conscious states can also cause things to happen to the brain. “Consequently, I wouldn’t want to say there’s a physical basis for religious experiences, even though they might be correlated. Sometimes it

could be cause-and-effect from brain to mind, but it could also be cause-and-effect from mind to brain. How do the scientists know it isn’t actually my prayer life that’s causing something to happen in my brain, rather than the other way around?” (For a further critique of “neurotheology,” the idea that the brain is wired for religious experiences, see: Kenneth L. Woodward, “Faith Is More Than a Feeling,” Newsweek, May 7, 2001).

THE RETURN OF OCKHAM’S RAZOR

As we talked about the human mind, mine was drifting back to my first interview with William Lane Craig, during which he brought up a scientific principle called Ockham’s razor. As I listened to Moreland defend the concept of dualism, it dawned on me that Ockham’s razor would argue in the opposite direction—toward the view that only the brain exists—because it says science prefers simpler explanations where possible. It was a challenge I decided to pose to Moreland. “You’re familiar with the scientific principle called Ockham’s razor,” I said to him. As soon as the question left my mouth, Moreland knew where I was headed.

“Yes, it says that we shouldn’t multiply entities beyond what’s needed to explain something. And I assume your objection is that Ockham’s razor would favor a simple alternative, such as the brain accounting for everything, rather than more complicated explanation like the two entities of dualism.” “That’s right,” I said. “Surely this undercuts the case for dualism.” He was ready with an answer. “No, it really doesn’t. Actually, Ockham’s razor favors dualism, and here’s why,” he said. “What’s the intent of Ockham’s razor? The thrust of this principle is that when you’re trying to explain a phenomenon, you should only include the elements that are necessary to explain the phenomenon. And as I’ve demonstrated through scientific evidence and philosophical reasoning, dualism is necessary to explain the phenomenon of consciousness.

Only dualism can account for all of the evidence—and, hence, it does not violate Ockham’s razor.” I wasn’t ready to give up. “But maybe we just don’t have all the evidence yet,” I said. “Maybe your conclusions are premature. Physicalists are confident that the day will come when they’ll be able to explain consciousness solely in physical terms.” Moreland’s reply was adamant: “There will never, ever be a scientific explanation for mind and consciousness.”

His forceful and unequivocal statement startled me. “Why not?” I asked. “Think about how scientists go about explaining things: they show that something had to happen due to antecedent conditions. For example,

when scientists explain why gases behave the way they do, they show that if you hold the volume constant and increase the temperature, the pressure has to increase. That is, when we heat a pressure cooker, the pressure goes up. “When scientists explain that, they don’t just correlate temperature and pressure. They don’t just say that temperature and pressure tend to go together. They try to show why the pressure has got to increase, why it couldn’t have done anything other than that, given the temperature increase. Scientists want to show why something has to happen given the cause; they’re not content simply to correlate things and leave it at that. “And this will never work with consciousness, because the relationship between the mind and the brain is contingent, or dependent.

In other words, the mind is not something that had to happen. One atheist asked, ‘How could a series of physical events, little particles jostling against one another, electric currents rushing to and fro, blossom into conscious experience? Why shouldn’t pain and itches be switched around? Why should any experience emerge when these neurons fire in the brain?’ He’s pointing out that there’s no necessary connection between conscious states and the brain. “So in the future scientists will be able to develop more correlations between conscious states and states of the brain, and that’s wonderful. But my point is this: correlation is not explanation. To explain something scientifically, you’ve got to show why the phenomenon had to happen given the causes. And scientists cannot explain the ‘why’ behind consciousness, because there’s no necessary connection between the brain and consciousness. It didn’t have to happen this way.”

DEDUCTIONS ABOUT GOD

It’s no wonder that Alvin Plantinga of Notre Dame University, a dualist who is frequently called the greatest living American philosopher, surveyed the current body/mind debate and concluded: “Things don’t look hopeful for Darwinian naturalists” (Quoted in Larry Witham, By Design, 211).

Faced with data and logic that support dualism, and unable to offer a plausible theory for how consciousness could have erupted from mindless matter, atheists are pinning their hopes on some as-yet-undetermined scientific discovery to justify their faith in physicalism. And some aren’t even so sure about that—physicist and atheist Steven Weinberg said scientists may have to “bypass the problem of human consciousness” altogether, because “it may just be too hard for us” (Ibid.,192).

In other words, it’s failing to give them the answers they want. As for Moreland, he agrees with Plantinga’s bleak assessment for atheists. “Darwinian evolution will never be able to explain the origin of consciousness,” he told me. “Perhaps Darwinists can explain how consciousness was shaped in a certain way over time, because the behavior that consciousness caused had survival value. But it can’t explain the origin of consciousness, because it can’t explain how you can get something from nothing.

“In Darwin’s notebooks, he said if there was anything his theory can’t explain, then there would have to be another explanation—a creationist explanation. Well, he can’t explain the origin of mind. He tried to reduce consciousness down to the brain, because he could tell a story about how the brain evolved. But as we’ve discussed, Lee, consciousness cannot be reduced merely to the physical brain. This means the atheist creation story is inadequate and false.

And yet there is an alternative explanation that makes sense of all the evidence: our consciousness came from a greater Consciousness. “You see, the Christian worldview begins with thought and feeling and belief and desire and choice. That is, God is conscious. God has thoughts. He has beliefs, he has desires, he has awareness, he’s alive, he acts with purpose. We start there. And because we start with the mind of God, we don’t have a problem with explaining the origin of our mind.” I asked, “What, then, can we deduce about God from this?” “That he’s rational, that he’s intelligent, that he’s creative, that he’s sentient. And that he’s invisible, because that’s the way conscious beings are. I have no inclination to doubt that this very room is teeming with the presence of God, just because I can’t see or touch or smell or hear him. As I explained earlier, I can’t even see my own wife! I can’t touch, see, smell, or hear the real her.

“One more thing. The existence of my soul gives me a new way to understand how God can be everywhere. That’s because my soul occupies my body without being located in any one part of it. There’s no place in my body where you can say, ‘Here I am.’ My soul is not in the left part of my brain, it’s not in my nose, it’s not in my lungs. My soul is fully present everywhere throughout my body. That’s why if I lose part of my body, I don’t lose part of my soul. “In a similar way, God is fully present everywhere. He isn’t located, say, right outside the planet Mars. God occupies space in the same way the soul occupies the body. If space were somehow cut in half, God wouldn‘t lose half his being. So now I have a new model, based on my own self, for God’s omnipresence. And shouldn’t we expect this? If we were made in the image of God, wouldn’t we expect there to be some parallels between us and God?” I asked, “Do you foresee more scientists coming to the conclusion that the soul, though immaterial, is very real?”

“The answer is yes—if they are willing to open themselves up to nonscientific knowledge,” he replied. “I believe in science; it’s wonderful and gives us some very important information. But there are other ways of knowing things as well. Because, remember, most of the evidence for the reality of consciousness and the soul is from our own first-person awareness of ourselves and has nothing to do with the study of the brain. The study of the brain allows us to correlate the brain with conscious states, but it tells us nothing about what consciousness itself is.”

“But, J. P., aren’t you asking scientists to do the unthinkable—to ignore scientific knowledge?” “No, not at all,” he insisted. “I’m only asking that they become willing to listen to all the evidence and see where it leads—which is what the quest for truth should be about.” “And if they do that?” “They will come to believe in the reality of the soul and the immaterial nature of consciousness. And this could open them up personally to something even more important—to a much larger Mind and a much bigger Consciousness, who in the beginning was the Logos, and who made us in his image.”

COGITO ERGO SUM

A ringing telephone ended our conversation, although I was wrapping up the interview anyway. A colleague was calling to remind Moreland of a faculty meeting. I thanked Moreland for his time and insights, gathered my things, and strolled out to my car. I was just about to start the engine, but instead I let go of the key, leaned back in my seat, and took a few moments (as Moreland would say) to introspect. Interestingly, this very act of introspection intuitively affirmed to me what Moreland’s facts and logic had already established—my ability to ponder, to reason, to speculate, to imagine, and to feel the emotional brunt of the interview showed that my mind surely could not have been the evolutionary byproduct of brute, mindless matter. “Selfhood . . . is not explicable in material or physical terms,” said philosopher Stuart C. Hackett. “The essential spiritual selfhood of man has its only adequate ground in the transcendent spiritual Selfhood of God as Absolute Mind” (Stuart C. Hackett, The Reconstruction of the Christian Revelation Claim. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 1984, 111).

In other words, I am more than just the sum total of a physical brain and body parts. Rather, I am a soul, and I have a body. I think—therefore, I am. Or as Hackett said: “With modest apology to Descartes: Cogito, ergo Deus est! I think, therefore God is” (Ibid). I found myself wholeheartedly agreeing with philosopher Robert Augros and physicist George Stanciu, who explored the depths of the mind/body controversy and concluded that “physics, neuroscience, and humanistic psychology all converge on the same principle: mind is not reducible to matter.” They added: “The vain expectation that matter might someday account for mind . . . is like the alchemist’s dream of producing gold from lead (Robert W. Augros and George N. Stanciu, The New Story of Science, 168, 171).

I leaned forward and started the car. After months of investigating scientific evidence for God—traveling a total of 26,884 miles, which is the equivalent of making one lap around the Earth at the equator—I had finally reached a critical mass of information. It was time to synthesize and digest what I had learned—and ultimately to come to a conclusion that would have vast and life-changing implications.

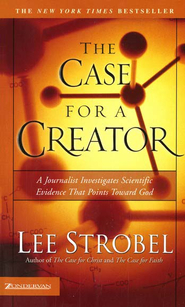

The interview of Lee Strobel (mini-bio below) with Dr. J. P. Moreland (mini-bio below) above is adapted from Chapter 10 in Lee Strobel. The Case for a Creator: A Journalist Investigates Scientific Evidence That Points Toward God. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009.

FOR FURTHER EVIDENCE

More Resources on This Topic

Cooper, John W. Body, Soul, and Life Everlasting. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1989.

Habermas, Gary and J. P. Moreland. Beyond Death. Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway, 1998.

Moreland, J. P. “God and the Argument from Mind.” In Scaling the Secular City. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 1987.

——. What Is the Soul? Norcross, Ga.: Ravi Zacharias International Ministries, 2002.

——. and Scott B. Rae. Body and Soul. Downer’s Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2000.

Taliaferro, Charles. Consciousness and the Mind of God. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Witham, Larry. “Mind and Brain.” In By Design: Science and the Search for God. San Francisco: Encounter Books, 2003.

About Lee Strobel

Atheist-turned-Christian Lee Strobel, the former award-winning legal editor of The Chicago Tribune, is a New York Times best-selling author of more than twenty books and has been interviewed on numerous national TV programs, including ABC, Fox, PBS, and CNN.

Described in the Washington Post as “one of the evangelical community’s most popular apologists,” Lee shared the Christian Book of the Year award in 2005 for a curriculum he co-authored with Garry Poole about the movie The Passion of the Christ. He also won Gold Medallions for his books The Case for Christ, The Case for Faith, and the The Case for a Creator, all of which have been made into documentaries distributed by Lionsgate.

His latest books include The Case for the Real Jesus, The Unexpected Adventure (co-authored with Mark Mittelberg) and The Case for Christ Study Bible, which includes hundreds of notes and articles on why Christians believe what they believe. His first novel, a legal thriller called The Ambition, came out in the Spring of 2011.

Lee was educated at the University of Missouri (Bachelor of Journalism degree, 1974) and Yale Law School (Master of Studies in Law degree, 1979). He was a professional journalist for 14 years at The Chicago Tribune and other newspapers, winning Illinois’ top honors for investigative reporting (which he shared with a team he led) and public service journalism from United Press International.

After a nearly two-year investigation of the evidence for Jesus, Lee became a Christian in 1981. He joined the staff of Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, IL, in 1987, and later became a teaching pastor there. He joined Saddleback Valley Community Church in Lake Forest, CA, as a teaching pastor in 2000. He left Saddleback’s staff to focus on writing.

Lee’s other books include God’s Outrageous Claims, The Case for Christmas, The Case for Easter, and Surviving a Spiritual Mismatch in Marriage, which he wrote with his wife, Leslie.

For two seasons, Lee was executive producer and host of the weekly national TV program Faith Under Fire.

Lee also is co-author of the Becoming a Contagious Christian course, which has trained more than a million Christians on how to naturally and effectively talk with others about Jesus. His articles have been published in a variety of magazines, including Discipleship Journal, Marriage Partnership, The Christian Research Journal, and Decision. He has appeared on such national radio programs as The Bible Answer Man and Focus on the Family. In addition, he has taught First Amendment law at Roosevelt University.

In recognition of his extensive research for his books, Southern Evangelical Seminary honored Lee with the conferring of a Doctor of Divinity degree in 2007.

Lee and Leslie have been married for 38 years and live in Colorado. Their daughter, Alison, is a novelist and co-author, with her husband Dan, of the children’s book, That’s Where God Is. Lee’s son, Kyle, holds two master’s degrees from the Talbot School of Theology and a PhD in theology from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. His first book was Metamorpha: Jesus as a Way of Life.

About Dr. J.P. Moreland (in his own words: http://www.jpmoreland.com/about/bio/)

I am the Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Talbot School of Theology, Biola University in La Mirada, California. I have four earned degrees: a B.S. in chemistry from the University of Missouri, a Th.M. in theology from Dallas Theological Seminary, an M. A. in philosophy from the University of California-Riverside, and a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Southern California.

During the course of my life, I have co-planted three churches, spoken and debated on over 175 college campuses around the country, and served with Campus Crusade for Christ for 10 years. For eight years, I served as a bioethicist for PersonaCare Nursing Homes, Inc. headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland.

My ideas have been covered by both popular religious and non-religious outlets, including the New Scientist and PBS’s “Closer to Truth,” Christianity TodayandWORLD magazine. I have authored or co-authored 30 books, including Kingdom Triangle, Scaling the Secular City, Consciousness and the Existence of God, The Recalcitrant Imago Dei, Love Your God With All Your Mind, The God Question, and Body and Soul. I have also published over 70 articles in journals, which include Philosophy and PhenomenologicalResearch,American Philosophical Quarterly, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Metaphilosophy, Philosophia Christi, andFaith and Philosophy.

Personal Interests

My hobbies are exercising, following the Kansas City Chiefs, and being fixated by really great TV dramas like 24 and Lost. With my dear wife and ministry partner, Hope, we have two married daughters, Ashley and Allison, and as of 2010, four grandchildren! We attend Vineyard Anaheim church and are deeply committed to the body of believers there.

On Who Has Influenced Me

Besides my family and close friends, three people have had the greatest impact on me during my journey with Jesus: Bill Bright, Howard Hendricks, and Dallas Willard. I first came to Christ in 1968, and joined Campus Crusade staff from 1970-75, and 1979-84. I will never forget being in Dr. Bright’s presence during those years. He exuded intimacy with the Lord, he was full of faith, and he lived a holy life. These values were clearly put in place in my life due to his influence. He set a high bar in these areas, and his life gave me a living hope that significant progress in these areas was clearly within reach. Dr. Bright also died a vibrant, victorious death, and as I age, I very much want to do the same in a Christ-honoring way.

I have the honor of studying under Dr. Hendricks during my years at Dallas Theological Seminary (DTS) from 1975-79. I took several courses from him and was in a small discipleship group with Hendricks my last year at DTS. The values I saw in him were radical commitment to Christ, to reading in general and studying scripture in particular, and to the priority of marriage and family. He also had a commitment not to bore people while teaching the Bible and to exhibiting a keen sense of humor. These have all become my values, due in no small measure to Dr. Hendricks.

However as much as Bright and Hendricks have impacted me, the influence of Dallas Willard towers over everyone else. I was honored to have him as my dissertation supervisor at the University of Southern California and Hope and I have counted Dallas and his wife Jane as dear friends and mentors for twenty-five years. Dallas impacted me in his combination of a rigorous intellect with a vibrant walk with Jesus, his fresh, penetrating ideas about the kingdom and how to live in it, and by the reality of God that pours out of his life. I cannot overstate my debt to him. All three were full of humility. It was and is clear that they are about something much bigger than they.

My Dearest Partner, My Wife

My wife, Hope, has been my friend and partner for now 33 years. We were married in 1977. She has the gifts of evangelism, encouragement, helps/mercy. I have never met someone who is consistently happier than she, who loves to care for and serve others, and who exhibits the warmth and kindness of the Holy Spirit. It may sound canned to say this, but it is the truth, namely, that my life and work simply are inconceivable without her love and care all these years. She simply makes my life possible. Or, as I wrote of her in my 1985 book dedication (Universals, Qualities, and Quality-Instances) to her:

Her gracious life truly fits her name and her soul exemplifies that range of qualities that truly wise persons everywhere know as the moral virtues

Well said, I might add! For I experience her unconditional love in an ongoing way. And God made her to be a mother and grandmother par excellence. It is a joy to see how her children honor, respect and love her. My daughters, Ashley and Allison, have turned out to be good, solid people. What impresses me most about both of them is their genuine concern for others and their ability to be good listeners. It isn’t all about them, and this is refreshing these days. Our girls not only love Hope and me, but they actually like us!! They, and their dear husbands, actually like being around us!! As of this writing, I have two grandchildren around three years old (a girl and a boy), a one-month old grandson, and a granddaughter due to be born October 2010. Does it get any better than this?

My Church

My love for the local church was not something that characterized me for much of my Christian life. I was primarily a parachurch guy and I wanted to get the job done, whether or not the local church was part of the solution. I was always committed to a sense of team, but my friendships were the primary source of fellowship for me and Hope within the body of Christ. But the last several years has been transforming.

My relationship with my local church—the Vineyard Anaheim—has shown me how short-sighted my previous vision was. I am fully committed to my local church’s well-being and absolutely love being a part of the fellowship. I have never been a “Lone Ranger Christian”—quite the opposite—but I now see more than ever the centrality of the local church to my intellectual, affective, and relational maturation. I thank God that He brought me to my senses.