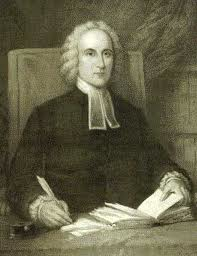

Edwards then turns his attention to the scriptural warrant for the doctrine of original sin. He pays particular attention to Paul’s teaching in Ephesians 2.

Another passage of the apostle, to the like purpose with that which we have been considering in the 5th [chapter] of Romans, is that in Ephesians 2:3—“And were by nature children of wrath, even as others.” This remains a plain testimony to the doctrine of original sin, as held by those who used to be called orthodox Christians, after all the pains and art used to torture and pervert it. This doctrine is here not only plainly and fully taught, but abundantly so, if we take the words with the context; where Christians are once and again represented as being, in their first state, dead in sin, and as quickened and raised up from such a state of death, in a most marvellous display of free rich grace and love, and exceeding greatness of God’s power, etc. (Ibid., 1:197, col. b.).

With respect to the uniform teaching of Scripture, Edwards concludes: “As this place in general is very full and plain, so the doctrine of the corruption of nature, as derived from Adam, and also the imputation of his first sin, are both clearly taught in it. The imputation of Adam’s one transgression, is indeed most directly and frequently asserted. We are here assured, that ‘by one man’s sin, death passed on all.’ … And it is repeated, over and over, that ‘all are condemned,’ ‘many are dead,’ ‘many made sinners,’ etc. ‘by one man’s offence,’ ‘by the disobedience of one,’ and ‘by one offence.’ ”

The Great Christian Doctrine of Original Sin Defended: Evidences of Its Truth Produced, and Arguments to the Contrary Answered … In

The Works of Jonathan Edwards, A.M. 10th ed. 2 vols. 1865. Reprint. Edinburgh / Carlisle, Penn.: Banner of Truth, 1979. 1:143–233.

Freedom of the Will. Edited by Paul Ramsey. The Works of Jonathan Edwards, edited by Perry Miller, vol. 1. New Haven and London: Yale University, 1957.

A Jonathan Edwards Reader. Edited by John E. Smith, Harry S. Stout, and Kenneth P. Minkema. New Haven: Yale University, 1995.

Finally Edwards argues for original sin from the biblical teaching regarding the application of redemption. The Spirit’s work in regeneration is a necessary antidote for a previous, corrupt condition: “It is almost needless to observe, how evidently this is spoken of as necessary to salvation, and as the change in which are attained the habits of true virtue and holiness, and the character of a true saint; as has been observed of regeneration, conversion, etc. and how apparent it is, that the change is the same.… So that all these phrases imply, having a new heart, and being renewed in the spirit, according to their plain signification” (Ibid., 1:214, col. a.).

In his introduction to the Yale edition of Edwards’s Freedom of the Will, Paul Ramsey makes this observation:

Into the writing of it he poured all his intellectual acumen, coupled with a passionate conviction that the decay to be observed in religion and morals followed the decline in doctrine since the founding of New England. The jeremiads, he believed, had better go to the bottom of the religious issue! The product of such plain living, high thinking, funded experience and such vital passion was the present Inquiry, a superdreadnaught which Edwards sent forth to combat contingency and self-determination (to reword [David F.] Swenson’s praise of one of [Søren] Kierkegaard’s big books) and in which he delivered the most thoroughgoing and absolutely destructive criticism that liberty of indifference, without necessity, has ever received. This has to be said even if one is persuaded that some form of the viewpoint Edwards opposed still has whereon to stand. This book alone is sufficient to establish its author as the greatest philosopher-theologian yet to grace the American scene (Paul Ramsey, “Editor’s Introduction,” in Jonathan Edwards, Freedom of the Will, ed. Paul Ramsey, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, ed. Perry Miller, vol. 1 (New Haven and London: Yale University, 1957), pp. 1–2. The full title of Edwards’s work was originally A Careful and Strict Enquiry into the Modern Prevailing Notions of That Freedom of Will, Which Is Supposed to Be Essential to Moral Agency, Virtue and Vice, Reward and Punishment, Praise and Blame. Ramsey alludes to David F. Swenson, translator of Søren Kierkegaard’s Philosophical Fragments (1936), Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1941), Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions (1941), volume 1 of Either/Or (1941), and Works of Love (1946); and author of Something about Kierkegaard (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1941).

In his own preface to Freedom of the Will, Edwards speaks of the danger of pinning labels on representatives of various schools of theological thought and the needless rancor often attached to such labels. Yet he pleads that generic terms are necessary for the sake of literary smoothness. A writer must have a shorthand way of distinguishing various characteristics of systems of thought. Although he does not agree with Calvin at every point, Edwards says he is not offended when labeled a Calvinist because he stands so squarely in that tradition.

His chief concern, however, is that the reader understand the consequences of differing theological perspectives. He regards the question of human freedom with the same earnestness Luther displayed in his debate with Erasmus. Far from being an isolated, peripheral, speculative matter, Edwards thinks this question is supremely important. He says:

The subject is of such importance, as to demand attention, and the most thorough consideration. Of all kinds of knowledge that we can ever obtain, the knowledge of God, and the knowledge of ourselves, are the most important. As religion is the great business, for which we are created, and on which our happiness depends; and as religion consists in an intercourse between ourselves and our Maker; and so has its foundation in God’s nature and ours, and in the relation that God and we stand in to each other; therefore a true knowledge of both must be needful in order to true religion. But the knowledge of ourselves consists chiefly in right apprehensions concerning those two chief faculties of our nature, the understanding and will. Both are very important: yet the science of the latter must be confessed to be of greatest moment; inasmuch as all virtue and religion have their seat more immediately in the will, consisting more especially in right acts and habits of this faculty. And the grand question about the freedom of the will, is the main point that belongs to the science of the will. Therefore I say, the importance of this subject greatly demands the attention of Christians, and especially of divines (Edwards, Freedom of the Will, p. 133).

Why We Choose

Edwards begins his inquiry by defining the will as “the mind choosing.” “… the will (without any metaphysical refining) is plainly, that by which the mind chooses anything,” he writes. “The faculty of the will is that faculty or power or principle of mind by which it is capable of choosing: an act of the will is the same as an act of choosing or choice” (Ibid., p. 137).

Even when a person does not choose a given option, the mind is choosing “the absence of the thing refused.” Edwards called these choices voluntary or “elective” actions.

John Locke asserted that “the will is perfectly distinguished from desire.” Edwards argues that will and desire are not “so entirely distinct, that they can ever be properly said to run counter. A man never, in any instance, wills anything contrary to his desires, or desires anything contrary to his will” (Ibid., p. 139. Quotes from John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 7th ed. [1716], 2.21.30).

This brief assertion is critical to understanding Edwards’s view of the will. He maintains that a man never chooses contrary to his desire. This means that man always acts according to his desire. Edwards indicates that the determining factor in every choice is the “strongest motive” present at that moment. In summary, we always choose according to the strongest motive or desire at the time.

People may debate this point with Edwards, recalling moments when they chose something they really did not want to choose. To understand Edwards, we must consider the complexities involved in making choices. Our desires are often complex and even in conflict with each other. Even the Apostle Paul experienced conflicting desires, claiming that what he wanted to do he failed to do and what he did not want to do he actually did (see Rom. 7:15). Does the apostle here belie Edwards’s point? I think not. Paul expresses the struggle he endures between desires in conflict. When he chooses what he “does not want to choose,” he is experiencing what I call the “all things being equal” dimension.

For example, every Christian has some desire in his heart to be righteous. All things being equal, we want always to be righteous. Yet a war is going on inside of us because we also continue to have wicked desires. When we choose the wicked over the righteous course of action, at that moment we desire the sin more than obedience to God. That was as true for Paul as it is for us. Every time we sin we desire more to do that than we do to obey Christ. Otherwise we simply would not sin.

Not only are desires not monolithic, but also they are not constant in their force or intensity. Our desire levels fluctuate from moment to moment. For example, the dieter desires to lose weight. After a full meal it is easy to say no to sweets. The appetite has been sated and the desire for more food diminished. As time passes, however, and self-denial has led to an increased hunger, the desire for food intensifies. The desire to lose weight remains. But when the desire to gorge oneself becomes stronger than the desire to lose weight, the dieter’s resolve weakens and he succumbs to temptation. All things do not remain in a constant state of equality.

Another example is a person being robbed. The robber points a gun at the person and says, “Your money or your life!” (We remember the skit made famous by Jack Benny. When posed with this option, Benny hesitated for a protracted time. In frustration the robber said, “What are you waiting for?” Benny replied, “I’m thinking it over.”) To be robbed at gunpoint is to experience a form of external coercion. The coercion reduces the person’s options to two. All things being equal, the person has no desire to donate the contents of his wallet to the thief. But with only two options the person will respond according to his strongest motive at the moment. He may conclude that if he refuses to hand over his wallet, the robber will both kill him and take his money. Most people will opt to hand the money over because they desire to live more than they desire to keep their wallets. It is possible, however, that a person has such a strong antipathy to armed robbery that he would prefer to die rather than give over his wallet “willingly.”

Related Works about Edwards

Gerstner, John H. The Rational Biblical Theology of Jonathan Edwards. 3 vols. Powhatan, Va.: Berea / Orlando: Ligonier, 1991–93.

Gerstner, John H. Jonathan Edwards: A Mini-Theology. Wheaton: Tyndale, 1987.

Lang, J. Stephen, ed. Jonathan Edwards and the Great Awakening. Christian History 4, 4 (1985).

Murray, Iain H. Jonathan Edwards: A New Biography. Edinburgh and Carlisle, Penn.: Banner of Truth, 1987.

Because this example contains a coercive dimension, I put the word willingly in quotation marks. We must ask if under these circumstances the action really is voluntary? It is if we view it in the context of only two options. However much external coercion is involved, there still remains a choice. Even here, Edwards would say, the person will choose the alternative for which he or she has the stronger motive.

The strongest-motive concept may be lost on us when we consider the manifold decisions we make every day without thoroughly considering the options available to us. We walk into a classroom where several seats are vacant or we walk to an unoccupied park bench and sit down. Rarely do we list the pros and cons before selecting a seat or a part of the bench. On the surface it seems that these choices are entirely arbitrary. We choose them without thinking. If that is so, it belies Edwards’s thesis that the will is the “mind choosing.”

Such choices seem to be mindless ones, but if we analyze them closely, we discover that some preference or motive is operating, albeit subtly. The motive factors may be so slight that they escape our notice. Experiments have been run in which people choose a seat on an unoccupied park bench. Some people always sit in the middle of the bench. Some are gregarious and long for company, so they choose the middle of the bench in hopes that someone will come along and sit beside them. And some people prefer solitude, so they sit in the middle in hopes that no one else will sit on the bench.

Likewise some people prefer to sit in the front of the classroom or the back for various reasons. The decision to select a certain seat is not an involuntary action like the beating of one’s heart. It is a voluntary action, which proceeds from some motive, however slight or obscure. In a word, there is a reason why we choose the seats we choose.

What Determines Our Choices

In his analysis of choices, Edwards discusses the determination of the will. He writes: “By ‘determining the will,’ if the phrase be used with any meaning, must be intended, causing that the act of the will or choice should be thus, and not otherwise: and the will is said to be determined, when, in consequence of some action, or influence, its choice is directed to, and fixed upon a particular object” (Edwards, Freedom of the Will, p. 141).

Edwards is not speaking of what is commonly called determinism, the idea that human actions are determined by some form of external coercion such as fate or manifest destiny. Rather he is here speaking of self-determination, which is the essence of human volition.

Edwards considers utterly irrational the idea that an “indifferent will” makes choices. “To talk of the determination of the will, supposes an effect, which must have a cause,” he says. “If the will be determined, there is a determiner. This must be supposed to be intended even by them that say, the will determines itself. If it be so, the will is both determiner and determined; it is a cause that acts and produces effects upon itself, and is the object of its own influence and action” (Ibid).

At this point Edwards argues from the vantage point of the law of cause and effect. Causality is presupposed throughout his argument. The law of cause and effect declares that for every effect there is an antecedent cause. Every effect must have a cause and every cause, in order to be a cause, must produce an effect. The law of causality is a formal principle that one cannot deny without embracing irrationality. David Hume’s famous critique of causality did not annihilate the law but our ability to perceive particular causal relationships.

The law of causality with which Edwards operates is “formal” in that it has no material content in itself and is stated in such a way as to be analytically true. That is, it is true by analysis of its terms or “by definition.” In this regard the law of causality is merely an extension of the law of noncontradiction. An effect, by definition, is that which has an antecedent cause. If it has no cause then it is not an effect. Likewise, a cause by definition is that which produces an effect. If no effect is produced then it is not a cause.

I once was criticized in a journal article by a scholar who complained, “The problem with Sproul is that he doesn’t allow for an uncaused effect.” I plead guilty to the charge, but I see this as virtue rather than vice. People who allow for uncaused effects are allowing for irrational nonsense statements to be true. If Sproul is guilty here, Edwards is more so. Edwards is far more cogent in his critical analysis of the intricacies of causality than Sproul will ever be in this life.

When Edwards declares that the will is both determined and determiner, he is not indulging in contradiction. The will is not determined and the determiner at the same time and in the same relationship. The will is the determiner in one sense and is determined in another sense. It is the determiner in the sense that it produces the effects of real choices. It is determined in the sense that those choices are caused by the motive that is the strongest one in the mind at the moment of choosing.

John H. Gerstner, perhaps the twentieth century’s greatest expert on Edwards, writes:

Edwards understands the soul to have two parts: understanding and will. Not only is Freedom of the Will based on this dichotomy; that dichotomy underlies Religious Affections as well.…

Edwards agreed with the English Puritan, John Preston, that the mind came first and the heart or will second. “Such is the nature of man, that no object can come at the heart but through the door of the understanding.…” In the garden, man could have rejected the temptation of the mind to move the will to disobey God. After the fall he could not, although Arminians and Pelagians thought otherwise. Their notion of the “freedom of the will” made it always possible for the will to reject what the mind presented. This perverted notion, Edwards said in Original Sin, “seems to be a grand favorite point with Pelagians and Arminians, and all divines of such characters, in their controversies with the orthodox.” For Edwards, acts of the will are not free in the sense of uncaused (John H. Gerstner, “Augustine, Luther, Calvin, and Edwards on the Bondage of the Will,” in Thomas R. Schreiner and Bruce A. Ware, eds., The Grace of God, the Bondage of the Will, 2 vols. [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1995], 2:291. Quotation from John Preston, “Sermon on Hebrews 5:12, ” in John Preston, Works, 2:158).

To Edwards a motive is “something that is extant in the view or apprehension of the understanding, or perceiving faculty” (Edwards, Freedom of the Will, p. 142).

He says:

… Nothing can induce or invite the mind to will or act anything, any further than it is perceived, or is some way or other in the mind’s view; for what is wholly unperceived, and perfectly out of the mind’s view, can’t affect the mind at all.…

… everything that is properly called a motive, excitement or inducement to a perceiving willing agent, has some sort and degree of tendency, or advantage to move or excite the will, previous to the effect, or to the act of the will excited. This previous tendency of the motive is what I call the “strength” of the motive.… that which appears most inviting, and has, by what appears concerning it to the understanding or apprehension, the greatest degree of previous tendency to excite and induce the choice, is what I call the “strongest motive.” And in this sense, I suppose the will is always determined by the strongest motive (Ibid).

Edwards further argues that the strongest motive is that which appears most “good” or “pleasing” to the mind. Here he uses good not in the moral sense, because we may be most pleased by doing what is not good morally. Rather the volition acts according to that which appears most agreeable to the person. That which is most pleasing may be deemed as pleasure. What entices fallen man to sin is the desire for some perceived pleasure.

Edwards then turns his attention to the terms necessity and contingency. He says “that a thing is … said to be necessary, when it must be, and cannot be otherwise” (Ibid., p. 149).

He goes beyond the ordinary use of the word necessary to the philosophical use. He says:

Philosophical necessity is really nothing else than the full and fixed connection between the things signified by the subject and predicate of a proposition, which affirms something to be true. When there is such a connection, then the thing affirmed in the proposition is necessary, in a philosophical sense; whether any opposition, or contrary effort be supposed, or supposable in the case, or no. When the subject and predicate of the proposition, which affirms the existence of anything, either substance, quality, act or circumstance, have a full and certain connection, then the existence or being of that thing is said to be necessary in a metaphysical sense. And in this sense I use the word necessity, in the following discourse, when I endeavor to prove that necessity is not inconsistent with liberty (Ibid., p. 152).

Edwards discusses various types of necessary connection. He observes that one type of connection is consequential: “things which are perfectly connected with other things that are necessary, are necessary themselves, by a necessity of consequence.” This is to say that if A is necessary and B is perfectly connected to A, then B is also necessary. It is only by such necessity of consequence that Edwards speaks of future necessities. Such future necessities are necessary in this way alone.

Similarly Edwards considers the term contingent. There is a difference between how the word is used in ordinary language and how it functions in philosophical discourse. He writes:

… Anything is said to be contingent, or to come to pass by chance or accident, in the original meaning of such words, when its connection with its causes or antecedents, according to the established course of things, is not discerned; and so is what we have no means of the foresight of. And especially is anything said to be contingent or accidental with regard to us, when anything comes to pass that we are concerned in, as occasions or subjects, without our foreknowledge, and beside our design and scope.

But the word contingent is abundantly used in a very different sense; not for that whose connection with the series of things we can’t discern, so as to foresee the event; but for something which has absolutely no previous ground or reason, with which its existence has any fixed and certain connection (Ibid., p. 155).

In ordinary language we attribute to accident or “chance” any unintended consequences. In a technical sense nothing occurs by chance, for chance has no being and can exercise no power. When the term contingent refers to effects with no ground or reason, it retreats to the assertion that there are effects without causes. It is one thing to say that we do not know what causes a given effect; it is quite another thing to say that nothing causes the effect. Nothing cannot do anything because it is not anything (See R. C. Sproul, Not a Chance: The Myth of Chance in Modern Science and Cosmology (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1994).

Our Moral Inability

One of the most important distinctions made by Edwards is the one between natural ability and moral ability. He also distinguishes between natural necessity and moral necessity. Natural necessity refers to those things that occur via natural force. Moral necessity refers to those effects that result from moral causes such as the strength of inclination or motive. He applies these distinctions to the issue of moral inability.

We are said to be naturally unable to do a thing, when we can’t do it if we will, because what is most commonly called nature [doesn’t] allow … it, or because of some impeding defect or obstacle that is extrinsic to the will; either in the faculty of understanding, constitution of body, or external objects. Moral inability consists not in any of these things; but either in the want of inclination; or the strength of a contrary inclination; or the want of sufficient motives in view, to induce and excite the act of the will, or the strength of apparent motives to the contrary. Or both these may be resolved into one; and it may be said in one word, that moral inability consists in the opposition or want of inclination (Edwards, Freedom of the Will, p. 159).

Man may have the desire to do things he cannot do because of limits imposed by nature. We may wish to be Superman, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound, more powerful than a locomotive, and faster than a speeding bullet. But unless we become fifteen-million-dollar men (up from six million due to inflation), it is highly unlikely that we will ever perform such prodigious feats. Nature enables birds to fly through the air without the aid of mechanical devices, and fish to live underwater without drowning. They are so constituted in their natures to be able to do these things. But we lack wings and feathers, or gills and fins. These are limitations imposed by nature. They reveal a lack or deficiency of necessary faculties or equipment.

Moral inability also deals with a deficiency, the lack of sufficient motive or inclination. Edwards cites various examples of moral inability: an honorable woman who is morally unable to be a prostitute, a loving child who is unwilling to kill his father, a lascivious man who cannot rein in his lust.

Given man’s moral inability, the will cannot not be free. The will is always free to act according to the strongest motive or inclination at the moment. For Edwards, this is the essence of freedom. To be able to choose what one desires is to be free in this sense. When I say the will cannot not be free, I mean the will cannot choose against its strongest inclination. It cannot choose what it does not desire to choose. Edwards refers to the common meaning of liberty: “… that power and opportunity for one to do and conduct as he will, or according to his choice.” The word says nothing of “the cause or original of that choice” (

Man may have the desire to do things he cannot do because of limits imposed by nature. We may wish to be Superman, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound, more powerful than a locomotive, and faster than a speeding bullet. But unless we become fifteen-million-dollar men (up from six million due to inflation), it is highly unlikely that we will ever perform such prodigious feats. Nature enables birds to fly through the air without the aid of mechanical devices, and fish to live underwater without drowning. They are so constituted in their natures to be able to do these things. But we lack wings and feathers, or gills and fins. These are limitations imposed by nature. They reveal a lack or deficiency of necessary faculties or equipment.

Moral inability also deals with a deficiency, the lack of sufficient motive or inclination. Edwards cites various examples of moral inability: an honorable woman who is morally unable to be a prostitute, a loving child who is unwilling to kill his father, a lascivious man who cannot rein in his lust.

Given man’s moral inability, the will cannot not be free. The will is always free to act according to the strongest motive or inclination at the moment. For Edwards, this is the essence of freedom. To be able to choose what one desires is to be free in this sense. When I say the will cannot not be free, I mean the will cannot choose against its strongest inclination. It cannot choose what it does not desire to choose. Edwards refers to the common meaning of liberty: “… that power and opportunity for one to do and conduct as he will, or according to his choice.” The word says nothing of “the cause or original of that choice” (Ibid., p. 164).

Edwards notes that Arminians and Pelagians have a different meaning for the term liberty. He lists a few aspects of their definition:

1. It consists in a self-determining power or a certain sovereignty the will has over itself, whereby it determines its own volitions.

2. Indifference belongs to liberty previous to the act of volition, in equilibrio.

3. Contingence belongs to liberty and is essential to it. Unless the will is free in this sense, it is deemed to be not free at all (Ibid., pp. 164–65).

Edwards then shows that the Pelagian notion is irrational and leads to an infinite regress of determination:

… If the will determines the will, then choice orders and determines the choice: and acts of choice are subject to the decision, and follow the conduct of other acts of choice. And therefore if the will determines all its own free acts, then every free act of choice is determined by a preceding act of choice, choosing that act. And if that preceding act of the will or choice be also a free act, then by these principles, in this act too, the will is self-determined; that is, this, in like manner, is an act that the soul voluntarily chooses.… Which brings us directly to a contradiction: for it supposes an act of the will preceding the first act in the whole train, directing and determining the rest; or a free act of the will, before the first free act of the will. Or else we must come at last to an act of the will, determining the consequent acts, wherein the will is not self-determined, and so is not a free act … but if the first act in the train … be not free, none of them all can be free.…

… if the first is not determined by the will, and so not free, then none of them are truly determined by the will.…(Ibid., pp. 172–73).

Edwards says the idea of an indifferent will is absurd. First, if the will functions from a standpoint of indifference, having no motive or inclination, then how can the choice be a moral one? If decisions are utterly arbitrary and done for no reason or motive, how do they differ from involuntary actions, or from the mere responses of plants, animals, or falling bodies?

Second, if the will is indifferent, how can there be a choice at all? If there is no motive or inclination, how can a choice be made? It requires an effect without a cause. For this reason, Edwards labors the question of whether volition can possibly arise without a cause through the activity of the nature of the soul. For Edwards it is axiomatic that “nothing has no choice.” “Choice or preference can’t be before itself, in the same instance, either in the order of time or nature,” he says. “It can’t be the foundation of itself, or the fruit or consequence of itself” (Ibid, p. 197).

Here Edwards applies the law of noncontradiction to the Pelagian and Arminian view of free will, and he shows that it is absurd. Indifference can only suspend choices, not create them. To create them would be to act ex nihilo, not only without a material cause, but also without a sufficient or efficient cause.

Edwards then treats several common objections to the Augustinian view, but we will not deal with them here. We conclude by summarizing Edwards’s view of original sin. Man is morally incapable of choosing the things of God unless or until God changes the disposition of his soul. Man’s moral inability is due to a critical lack and deficiency, namely the motive or desire for the things of God. Left to himself, man will never choose Christ. He has no inclination to do so in his fallen state. Since he cannot act against his strongest inclination, he will never choose Christ unless God first changes the inclination of his soul by the immediate and supernatural work of regeneration. Only God can liberate the sinner from his bondage to his own evil inclinations.

Like Augustine, Luther, and Calvin, Edwards argues that man is free in that he can and does choose what he desires or is inclined to choose. But man lacks the desire for Christ and the things of God until God creates in his soul a positive inclination for these things.

The Article above was adapted from chapter 7 of R.C. Sproul. Willing to Believe: The Controversy Over Free Will. Grand Rapids, Baker, 1997.

About the Author:

Dr. R.C. Sproul (Founder of Ligonier Ministries; Bible College and Seminary President and Professor; and Senior Minister at Saint Andrews in Sanford, Florida) is an amazingly gifted communicator. Whether he is teaching, preaching, or writing – he has the ability to make the complex easy to understand and apply. He has been used more than any other person in my life to deepen my walk with Christ and help me to be more God-centered than man-centered. His book the Holiness of God has been the most influential book in my life – outside of the Bible.