If systematic Dispensationalism is rightly understood it logically makes sense only within a theocentric and soteriologically Calvinists theology. Dispensationalism teaches that it is GOD who is ruling His household, as administered through the various dispensations of history. Though Dispensationalism, or elements of Dispensationalism have been disseminated throughout a wide diversity of Protestant traditions, this system of theology is best seen as a system of theology that views God as the Sovereign ruler of heaven and earth; man as a rebellious vice-regent (along with some angels); Jesus Christ is the hero of history as He is saves some by His Grace; history as a lesson in the outworking of God’s glory being displayed to both heaven and earth. In essence, Dispensationalism is a theology properly derived from biblical study and lets God be God.

Modern, systematic Dispensationalism is approaching two hundred years of expression and development. We live at a time in which Dispensationalism and some of its ideas have been disseminated and adopted by various theological traditions. This is not surprising since our day is characterized by anti-systemization and eclecticism in the area of thought. It may be surprising, to some, to learn that Dispensationalism was developed and spread during its first 100 years by those within a Reformed, Calvinistic tradition. It had only been in the last 75 to 50 years that Dispensationalism and some of its beliefs were disseminated in any significant way outside of the sphere of Calvinism.

Definitions

Before proceeding further I need to provide working definitions of what I mean by Calvinism and Dispensationalism.

First, by Calvinism, I am speaking mainly of the theological system that relates to the doctrine of grace or soteriological Calvinism. This would include strict and modified Calvinism (i.e. four and five point Calvinism [some hold to limited atonement and some hold to universal atonement]). I am referring to that aspect of Calvinism that speaks of the fallen nature of man and the elective grace of God (John Calvin image at left).

First, by Calvinism, I am speaking mainly of the theological system that relates to the doctrine of grace or soteriological Calvinism. This would include strict and modified Calvinism (i.e. four and five point Calvinism [some hold to limited atonement and some hold to universal atonement]). I am referring to that aspect of Calvinism that speaks of the fallen nature of man and the elective grace of God (John Calvin image at left).

Second, by Dispensationalism, I have in mind that system of  theology that was developed by J. N. Darby (pictured on right) that gave rise to its modern emphasis of consistent literal interpretation, a distinction between God’s plan for Israel and the church, usually a pretribulational rapture of the church before the seventieth week of Daniel, premillennialism, and a multifaceted emphasis upon God’s glory as the goal of history. This includes some who have held to such a system but may have stop short of embracing pretribulationism. The focus of this article will be upon Dispensational premillennialism.

theology that was developed by J. N. Darby (pictured on right) that gave rise to its modern emphasis of consistent literal interpretation, a distinction between God’s plan for Israel and the church, usually a pretribulational rapture of the church before the seventieth week of Daniel, premillennialism, and a multifaceted emphasis upon God’s glory as the goal of history. This includes some who have held to such a system but may have stop short of embracing pretribulationism. The focus of this article will be upon Dispensational premillennialism.

Theological Logic

In concert with the Calvinist impulse to view history theocentricly, I believe that dispensational premillennialism provides the most logical eschatological ending to God’s sovereign decrees for salvation and history. Since Dispensational premillennialists view both the promises of God’s election of Israel and the church as unconditional and something that God will surely bring to pass, such a belief is consistent with the Bible and logic. A covenant theologian would say that Israel’s election was conditional and temporary. Many Calvinists are covenant theologians who think that individual election within the church is unconditional and permanent. They see God’s plan with Israel conditioned upon human choice, while God’s plan for salvation within the church is ultimately a sovereign act of God. There is no symmetry in such logic. Meanwhile, Dispensational premillennialists see both acts as a sovereign expression of God’s plan in history that is a logical, consistent application of the sovereign will of God in human affairs.

Samuel H. Kellogg, a Presbyterian minister, missionary, and educator wrote of the logic between Calvinism and “modern, futurist premillennialism,” which was in that day (1888) essentially dispensational. “But in general,” notes Kellogg, “we think, it may be rightly said that the logical relations of premillennialism connect it more closely with the Augustinianthan with any other theological system” (Samuel H. Kellogg, “Premillennialism: Its relations to Doctrine and Practice,” Bibliotheca Sacra, XLV [1888], p. 253).

His use of “Augustinian” is the older term for Calvinism. Kellogg points out the different areas in which Calvinism and premillennialism are theologically one. “Premillennialism logically presupposes an anthropology essentially Augustinian. The ordinary Calvinism affirms the absolute helplessness of the individual for self-regeneration and self- redemption” (Kellogg, “Premillennialism,” p. 254). He continues, “it is evident that the anthropological presuppositions on which premillennialism seems to rest, must carry with them a corresponding soteriology” (Kellogg, “Premillennialism,” p. 257). Kellogg reasons that “the Augustinian affinity of the premillennialist eschatology becomes still more manifest. Nothing is more marked than the emphasis with which premillennialists constantly insist that, the present dispensation is strictly elective” (Kellogg, “Premillennialism,” p. 258-59). “In a word,” concludes Kellogg, “we may say that premillennialists simply affirm of the macrocosm what the common Augustinianism affirms only of the microcosm” (Kellogg, “Premillennialism,” p. 256).

This is not to say that Dispensationalism and Calvinism are synonymous. I merely contend that it is consistent with certain elements of Calvinism that provide a partial answer as to why Dispensationalism sprang from the Reformed tradition. C. Norman Kraus contends,

There are, to be sure, important elements of seventeenth-century Calvinism in contemporary dispensationalism, but these elements have been blended with doctrinal emphasis from other sources to form a distinct system which in many respects is quite foreign to classical Calvinism (C. Norman Kraus, Dispensationalism in America: Its Rise and Development. Richmond: John Knox Press, 1958, p. 59).

Nevertheless, Dispensationalism did develop within the Reformed community and most of its adherents during the first 100 years were from within the Calvinist milieu. Kraus concludes: “Taking all this into account, it must still be pointed out that the basic theological affinities of dispensationalism are Calvinistic. The large majority of men involved in the Bible and prophetic conference movements subscribed to Calvinistic creeds” (Ibid). I will now turn to an examination of some of the founders and proponents of Dispensationalism?

Darby and the Brethren

Modern systematic dispensationalism was developed in the 1830s by J. N. Darby and those within the Brethren movement. Virtually all of these men came from churches with a Calvinistic soteriology. “At the level of theology,” says Brethren historian H. H. Rowdon, “the earliest Brethren were Calvinists to a man” (Harold H. Rowdon, Who Are The Brethren and Does it Matter? Exeter, England: The Paternoster Press, 1986, p. 35). This is echoed by one of the earliest Brethren, J. G. Bellett, who was beginning his association with the Brethren when his brother George wrote, “for his views had become more decidedly Calvinistic, and the friends with whom he associated in Dublin were all, I believe without exception, of this school” (George Bellett, Memoir of the Rev. George Bellett . London: J. Masters, 1889, pp. 41–2, cited in Max S. Weremchuk, John Nelson Darby. Neptune, N.J.: Loizeaux Brothers, 1992, p. 237, f.n. 25).

What were Darby’s views on this matter? John Howard Goddard observes that Darby “held to the predestination of individuals and that he rejected the Arminian scheme that God predestinated those whom he foreknew would be conformed to the image of Christ.” In his “Letter on Free-Will,” it is clear that Darby rejects this notion. “If Christ has come to save that which is lost, free-will has no longer any place.” “I believe we ought to hold to the word;” continues Darby, “but, philosophically and morally speaking, free-will is a false and absurd theory. Free-will is a state of sin” (Ibid, p. 186). Because Darby held to the bondage of the will, he logically follows through with belief in sovereign grace as necessary for salvation.

Such is the unfolding of this principle of sovereign grace, without which not one should would be saved, for none understand, none seek after God, not one of himself will come that he might have life. Judgment is according to works; salvation and glory are the fruit of grace (J. N. Darby, “Notes on Romans,” in The Collected Writings of J. N. Darby [Winschoten, Netherlands: H. L. Heijkoop, 1971], 26: 107–8).

Further evidence of Darby’s Calvinism is that on at least two occasions he was invited by non-dispensational Calvinists to defend Calvinism for Calvinists. One of Darby’s biographers, W. G. Turner spoke of his defense at Oxford University:

It was at a much earlier date (1831, I think) that F. W. Newman invited Mr. Darby to Oxford: a season memorable in a public way for his refutation of Dr. E. Burton’s denial of the doctrines of grace, beyond doubt held by the Reformers, and asserted not only by Bucer, P. Martyr, and Bishop Jewell, but in Articles IX—XVIII of the Church of England (W. G. Turner, John Nelson Darby: A Biography [London: C. A. Hammond, 1926], p. 45).

On another occasion Darby was invited to the city of Calvin—Geneva, Switzerland—to defend Calvinism. Turner declares, “He refuted the ‘perfectionism’ of John Wesley, to thedelight of the Swiss Free Church.” Darby was awarded a medal of honor by the leadership of Geneva (Rowdon, Who Are The Brethren, pp. 205–07).

Still yet, when certain Reformed doctrines came under attack from within the Church in which he once served, “Darby indicates his approval of the doctrine of the Anglican Church as expressed in Article XVII of the Thirty-Nine Articles” (Goddard, “The Contribution of Darby,” p. 86). On the subject of election and predestination, Darby said,

For my own part, I soberly think Article XVII to be as wise, perhaps I might say the wisest and best condensed human statement of the view it contains that I am acquainted with. I am fully content to take it in its literal and grammatical sense. I believe that predestination to life is the eternal purpose of God, by which, before the foundations of the world were laid, He firmly decreed, by His counsel secret to us, to deliver from curse and destruction those whom He had chosen in Christ out of the human race, and to bring them, through Christ, as vessels made to honour, to eternal salvation (J. N. Darby, “The Doctrine of the Church of England at the Time of the Reformation,” in The Collected Writings of J. N. Darby [Winschoten, Netherlands: H. L. Heijkoop, 1971], 3:3).

Dispensationalism in America

Darby and other Brethren brought dispensationalism to America through their many trips and writings that came across the Atlantic. “In fact the millenarian (or dispensational premillennial) movement,” declares George Marsden, “had strong Calvinistic ties in its American origins” (George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism: 1870–1925 [New York: Oxford University Press, 1980], p. 46). Reformed historianMarsden continues his explanation of how dispensationalism came to America:

This enthusiasm came largely from clergymen with strong Calvinistic views, principally Presbyterians and Baptists in the northern United States. The evident basis for this affinity was that in most respects Darby was himself an unrelenting Calvinist. His interpretation of the Bible and of history rested firmly on the massive pillar of divine sovereignty, placing as little value as possible on human ability (Ibid).

The post-Civil War spread of dispensationalism in North America occurred through the influence of key pastors and the Summer Bible Conferences like Niagara, Northfield, and Winona. Marsden notes:

The organizers of the prophetic movement in America were predominantly Calvinists. In 1876 a group led by Nathaniel West, James H. Brookes, William J. Eerdman, and Henry M. Parsons, all Presbyterians, together with Baptist A. J. Gordon, …These early gatherings, which became the focal points for the prophetic side of their leaders’ activities, were clearly Calvinistic. Presbyterians and Calvinist Baptists predominated, while the number of Methodists was extremely small… Such facts can hardly be accidental (Ibid).

Proof of Marsden’s point above is supplied by Samuel H. Kellogg—himself a Presbyterian and Princeton graduate—with his breakdown of the predominately dispensational Prophecy Conference in New York City in 1878. Kellogg classified the list of those that signed the call for the Conference as follows (Kellogg, “Premillennialism,” p. 25):

| Reformed Episcopalians |

10 |

| Congregationalists |

10 |

| Methodists |

6 |

| Adventists |

5 |

| Lutheran |

1 |

| Presbyterians |

31 |

| United Presbyterians |

10 |

| Reformed (Dutch) |

3 |

| Episcopalians |

10 |

| Baptist |

22 |

Kellogg concluded that “the proportion of Augustinians in the whole to be eighty-eight per cent” (Ibid, p. 254). “The significance of this is emphasized,” continues Kellogg, “by the contrasted fact that the Methodists, although one of the largest denominations of Christians in the country, were represented by only six names” (Ibid). Kellogg estimates that “analyses of similar gatherings since held on both sides of the Atlantic, would yield a similar result” (Ibid).

George Marsden divides Reformed Calvinism in America into three types: “doctrinalist, culturalist, and pietist” (George M. Marsden, “Introduction: Reformed and American,” in David F. Wells, ed., Reformed Theology in America: A History of Its Modern Development [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1997], p. 3). He then explains that “Dispensationalism was essentially Reformed in its nineteenth-century origins and had in later nineteenth-century America spread most among revival-oriented Calvinists” (Ibid, p. 8). This is not to say that only revival-oriented Calvinists were becoming dispensational in their view of the Bible and eschatology. Ernest Sandeen lists at least one Old School Presbyterian—L. C. Baker of Camden, New Jersey—as an active dispensationalist during the later half of the nineteenth century (Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1970]).

Timothy Weber traces the rise of Dispensationalism as follows:

The first converts to dispensational premillennialism after the Civil War were pietistic evangelicals who were attracted to its Biblicism, its concern for evangelism and missions, and its view of history, which seemed more realistic than that of the prevailing postmillennialism. Most of the new premillennialists came from Baptist, New School Presbyterian, and Congregationalist ranks, which gave the movement a definite Reformed flavor. Wesleyan evangelicals who opposed premillennialism used this apparent connection to Calvinism to discredit it among Methodists and holiness people (Timothy P. Weber, “Premillennialism and the Branches of Evangelicalism,” in Donald W. Dayton and Robert K Johnston, editors, The Variety of American Evangelicalism [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press]).

It is safe to say that without the aid of Reformed Calvinists in America dispensational premillennialism would have had an entirely different history. Men like the St. Louis Presbyterian James H. Brookes (1830–1897), who was trained at Princeton Seminary, opened his pulpit to Darby and other speakers. Brookes, considered the American father of the pretribulational rapture in America, also discipled a new convert to Christ in the legendary C. I. Scofield (For more on the life of Brookes see Larry Dean Pettegrew, “The Historical and Theological Contributions of the Niagara Bible Conference to American Fundamentalism,” [Th.D. Dissertation from Dallas Theological Seminary, 1976]; David Riddle Williams, James H. Brookes: A Memoir, [St. Louis: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1897]). Others such as Presbyterians Samuel H. Kellogg (Princeton trained), E. R. Craven, who was a PrincetonCollege and Seminary graduate and Old School Presbyterian (Samuel Macauley Jackson, ed., The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1952], 3: 296), and Nathaniel West provided great leadership in spreading dispensationalism in the late 1800s.

Scofield, Chafer, and Dallas Seminary

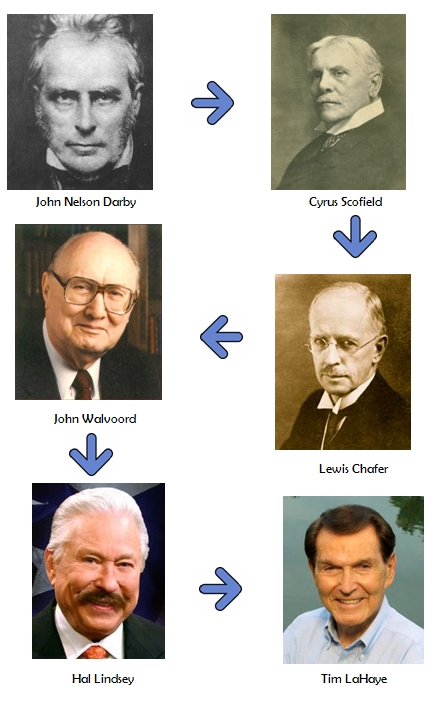

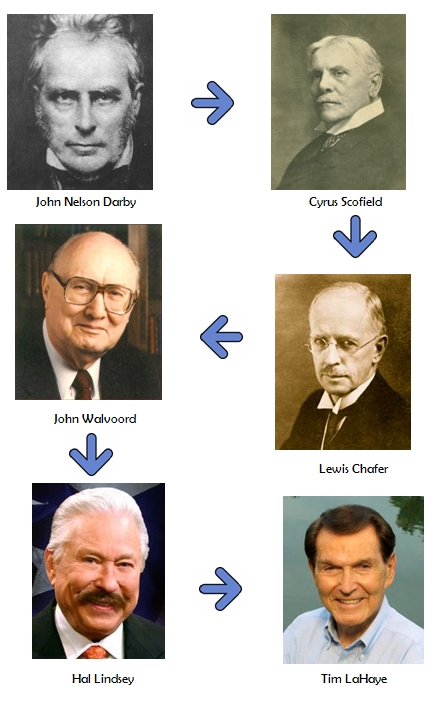

C. I. Scofield (1843–1921), Lewis Sperry Chafer (1871–1952), and Dallas Theological Seminary (est. 1924) were great vehicles for the spread of dispensationalism in America and throughout the world. Both Scofield and Chafer were ordained Presbyterian ministers. The “Scofield Reference Bible, is called by many the most effective tool for the dissemination of dispensationalism in America” (Larry V. Crutchfield, The Origins of Dispensationalism: The Darby Factor, [Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1992], preface). Scofield was converted in mid-life and first discipled by James H. Brookes in St. Louis. He was ordained to the ministry at the First Congregational Church of Dallas in 1882 and transferred his ministerial credentials to the Presbyterian Church in the U. S. in 1908 (Daniel Reid, ed., Dictionary of Christianity in America [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1990], pp. 1057–58). Thus, his ministry took place within a Calvinistic context (Chart of some of the biggest popularizers of Dispensationalism pictured left – Darby, Scofield, Chafer were Calvinists – not certain about the others).

C. I. Scofield (1843–1921), Lewis Sperry Chafer (1871–1952), and Dallas Theological Seminary (est. 1924) were great vehicles for the spread of dispensationalism in America and throughout the world. Both Scofield and Chafer were ordained Presbyterian ministers. The “Scofield Reference Bible, is called by many the most effective tool for the dissemination of dispensationalism in America” (Larry V. Crutchfield, The Origins of Dispensationalism: The Darby Factor, [Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1992], preface). Scofield was converted in mid-life and first discipled by James H. Brookes in St. Louis. He was ordained to the ministry at the First Congregational Church of Dallas in 1882 and transferred his ministerial credentials to the Presbyterian Church in the U. S. in 1908 (Daniel Reid, ed., Dictionary of Christianity in America [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1990], pp. 1057–58). Thus, his ministry took place within a Calvinistic context (Chart of some of the biggest popularizers of Dispensationalism pictured left – Darby, Scofield, Chafer were Calvinists – not certain about the others).

Scofield was the major influence upon the development of Chafer’s theology. John Hannah notes that “it is impossible to understand Chafer without perceiving the deep influence of Scofield” (John David Hannah, “The Social and Intellectual History of the Origins of the Evangelical Theological College,” [Ph. D. Dissertation from The University of Texas at Dallas, 1988], pp. 118–19). In fact, “Chafer often likened this relationship to that of father and a son” (Jeffrey J. Richards, The Promise of Dawn: The Eschatology of Lewis Sperry Chafer, [Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1991], p. 23). This relationship grew out of Chafer’s study under Scofield at the Northfield Conference and from a life-changing experience in Scofield’s study of the First Congregational Church of Dallas in the early 1900s. Scofield toldChafer that his gifts were more in the field of teaching and not in the area of evangelism in which he had labored. “The two prayed together, and Chafer dedicated his life to a lifetime of biblical study” (Ibid).

Scofield and Chafer were two of the greatest American dispensationalists and both developed their theology from out of a Reformed background. Scofield is known for his study bible and Chafer for his Seminary and systematic theology. Jeffrey Richards describes Chafer’s theological characteristics as having “much in common with the entire Reformed tradition. Excluding eschatology, Chafer is similar theologically to such Princeton divines as Warfield, Hodge, and Machen. He claims such doctrines as the sovereignty of God, …total depravity of humanity, election, irresistible grace, and the perseverance of the saints” (Ibid, p.3). C. Fred Lincoln describes Chafer’s 8-volume Systematic Theology as “unabridged, Calvinistic, premillennial, and dispensational” (C. F. Lincoln, “Biographical Sketch of the Author,” in Lewis Sperry Chafer, Systematic Theology [Dallas: Dallas Seminary Press, 1948], 8:6).

Since its founding in 1924 as The Evangelical Theological College (changed to Dallas Theological Seminary in 1936), it has exerted a global impact on behalf of dispensationalism. Dallas Seminary’s primary founder was Chafer, but William Pettingill and W. H. Griffith-Thomas also played a leading role. Pettingill, like Chafer, was Presbyterian. Griffith Thomas, an Anglican, wrote one of the best commentaries on the Thirty-nine Articles of the Anglican Church (W. H. Griffith Thomas, The Principles of Theology: An Introduction to the Thirty-nine Articles [Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1979/1930]), which is still widely used by conservative Anglicans and Episcopalians today. The Thirty-nine Articles are staunchly Calvinistic. Both men were clearly Calvinists. The seminary, especially before World War II, considered itself Calvinistic. Chafer once characterized the school in a publicity brochure as “in full agreement with the Reformed Faith and itstheology is strictly Calvinistic.” In a letter to Allan MacRae of Westminster Theological Seminary, Chafer said, “You probably know that we are definitely Calvinistic in our theology” (Cited in Ibid, p. 200). “Speaking of the faculty, Chafer noted in 1925 that they were ‘almost wholly drawn from the Southern and Northern Presbyterian Churches’“ (Cited in Ibid., p. 346). Further, Chafer wrote to a Presbyterian minister the following: “I am pleased to state that there is no institution to my knowledge which is more thoroughly Calvinistic nor more completely adjusted to this system of doctrine, held by the Presbyterian Church” (Ibid., p. 346, footnote 323).

Since so many early Dallas graduates entered the Presbyterian ministry, there began to be a reaction to their dispensational premillennialism in the 1930s. This was not an issue as to whether they were Calvinistic in their soteriology, but an issue over their eschatology. In the late 1930s, “Dallas Theological Seminary, though strongly professing to be a Presbyterian institution, was being severed from the conservative Presbyterian splinter movement” (Ibid, pp. 357-358). In 1944, Southern Presbyterians issued a report from a committee investigating the compatibility of dispensationalism with the Westminster Confession of Faith. The committee ruled dispensationalism was not in harmony with the Church’s Confession. This “report of 1944 was a crippling blow to any future that dispensational premillennialism might have within Southern Presbyterianism” (Ibid, 364). This ruling effectively moved Dallas graduates away from ministry within Reformed denominations toward the independent Bible Church movement.

A Broadening of Dispensational Acceptance

Even though dispensationalism had made a modest penetration of Baptists as early as the 1880s through advocates such as J. R. Graves (See J. R. Graves, The Work of Christ Consummated in 7 Dispensations [Memphis: Baptist Book House, 1883]), a strong Calvinist, they were rebuffed by non-Calvinists until the mid-1920s when elements of dispensational theology began to be adopted by some Pentecostals in an attempt to answer the increasing threat of liberalism. Kraus explains:

Some teachers said explicitly that premillennialism was a bulwark against rationalist theology. Thus it is not surprising to find that the theological elements which became normative in dispensationalism ran directly counter to the developing emphasis of the “New Theology” (Kraus, Dispensationalism, p. 61).

Up to this point in history, those from the Arminian and Wesleyan traditions were more interested in present, personal sanctification issues, rather than the Calvinist attention in explaining God’s sovereign work in the progress of history. However, the rise of the fundamentalist/liberal controversy in the 1920s stirred an interest, outside of the realm of Calvinism, in defending the Bible against the anti-supernatural attacks of the liberal critics. Dispensationalism was seen as a conservative and Bible-centered answer to liberalism, not only within fundamentalism, but increasingly by Pentecostals and others as well. Timothy Weber notes:

But in time, dispensationalism had its devotees within the Wesleyan tradition as well. More radical holiness groups resonated with its prediction of declining orthodoxy and piety in the churches; and Pentecostals found in it a place for the outpouring of the Spirit in a “latter-day rain” before the Second Coming (Weber, “Premillennialism,” p. 15).

Latter Rain Pentecostalism

One of the first non-Calvinist groups to adopt a dispensational orientation can be found among some Pentecostals in the mid-1920s. This development must be understood against a backdrop of the Wesleyan and holiness heritage out of which Pentecostalism arose at the turn of last century. The American holiness movement of the 1800s was primarily postmillennial and if premillennial, then historical premillennial. They were not in any way dispensational.

Pentecostalism is at heart a supposed restoration of apostolic Christianity that is meant to bring in the latter rain harvest in preparation for Christ’s return. The phrase “latter rain” is taken from Joel 2:23 & 28 and sometimes James 5:7 as a label describing an end-time revival and evangelistic harvest expected by many charismatics and Pentecostals. Some time in the future, they believe the Holy Spirit will be poured out like never before. The latter rain teaching is developed from the agricultural model that a farmer needs rain at two crucial points in the growing cycle in order to produce a bountiful harvest. First, right after the seed is planted the “early rain” is needed to cause the seed to germinate in order to produce a healthy crop. Second, the crop needs rain right before the harvest, called the “latter rain,” so the grain will produce a high yield at harvest time, which shortly follows. Latter rain advocates teach that the Acts 2 outpouring of the Holy Spirit was the “early rain” but the “latter rain” outpouring of the Holy Spirit will occur at the end-times. This scenario is in conflict with dispensationalism that sees the current age ending, not in revival, but apostasy. It will be during the tribulation, after the rapture of the church, that God will use the miraculous in conjunction with the preaching of the gospel. Thus, latter rain theology fits within a postmillennial or historical premillennial eschatology, but it is not consistent with dispensationalism.

Many Christians are aware that the Pentecostal movement began on January 1, 1901 in Topeka, Kansas when Agnes Ozman (1870–1937) spoke in tongues under the tutelage of Charles Fox Parham (1873–1929). Yet, how many realize that in the “early years Movement’” (Donald Dayton, Theological Roots of Pentecostalism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1987), p. 27)? This is because Parham titled his report of the new movement as “The Latter Rain: The Story of the Origin of the Original Apostolic or Pentecostal Movements” (Dayton, Roots, pp. 22–23). Many are also aware that William J. Seymour (1870–1922) came under the influence of Parham in Houston, Texas in 1905 and then took the Pentecostal message to Azusa Street in Los Angeles in 1906, from where it was disseminated to the four-corners of the world. But, how many are also aware that he too spoke of these things in terms of a latter rain framework?

There is no doubt that the latter rain teaching was one of the major components—if not the major distinctive—in the theological formation of Pentecostalism. “Modern Pentecostalism is the ‘latter rain,’ the special outpouring of the Spirit that restores the gifts in the last days as part of the preparation for the ‘harvest,’ the return of Christ in glory,” says Donald Dayton (Ibid, 27). David Wesley Myland (1858–1943) was one of the early Pentecostal leaders. He wrote the first distinctly Pentecostal hymn entitled, “The Latter Rain” in 1906. The “first definitive Pentecostal theology that was widely distributed, the Latter Rain Covenant” appeared in 1910 (Stanley M. Burgess and Gary B. McGee, editors, Dictionary of Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1988], p. 632). Myland argued in his book that “now we are in the Gentile Pentecost, the first Pentecost started the church, the body of Christ, and this, the second Pentecost, unites and perfects the church into the coming of the Lord” (Cited by Dayton, Roots, p. 27).

Dayton concludes that the “broader Latter Rain doctrine provided a key…premise in the logic of Pentecostalism” (Ibid). In spite of having such a key place in the thinking of early Pentecostalism, “the latter rain doctrine did tend to drop out of Pentecostalism” in the 1920s “only to reappear, however, in the radical Latter Rain revitalization movement of the 1940s” (Ibid, 43). One of reasons that latter rain teachings began to wane in the mid-1920s was that as Pentecostalism became more institutionalized it needed an answer to the inroads of liberalism. As noted above, dispensationalism was seen helpful in these areas.

The Latter Rain teaching developed out of the Wesleyan-Holiness desire for both individual (sanctification) and corporate (eschatological) perfection. Thus, early perfectionist teachers like John Wesley, Charles Finney, and Asa Mahan were all postmillennial and social activists. Revivalism was gagged by carrying the burden of both personal and public change or perfection. It follows that one who believes in personal perfection should also believe that public perfection is equally possible. Those who believe the latter are postmillennialists. After all, if God has given the Holy Spirit in this age to do either, then why not the other? If God can perfect individuals, then why not society?

However, as the 1800s turned into the 1900s, social change was increasingly linked with Darwin’s theory of evolution. The evolutionary rationale was then used to attack the Bible itself. To most English-speaking Christians it certainly appeared that society was not being perfected, instead it was in decline. Critics of the Bible said that one needed a Ph.D. from Europe before the Bible could be organized and understood. It was into this climate that dispensationalism was introduced into America and probably accounts for its speedy and widespread acceptance by many conservative Christians. To many Bible believing Christians, Dispensationalism made a great deal more sense of the world than did the anti-supernaturalism conclusions of liberalism.

Dispensationalism, in contrast to Holiness teaching, taught that the world and the visible church were not being perfected, instead Christendom was in apostasy and heading toward judgment. God is currently in the process of calling out His elect through the preaching of the gospel. Christian social change would not be permanent, nor would it lead to the establishment of Christ’s kingdom before His return. Instead a cataclysmic intervention was needed (Christ’s second coming), if society was to be transformed.

Early Pentecostalism was born out of a motivation and vision for restoring to the church apostolic power lost over the years. Now she was to experience her latter-day glory and victory by going out in a blaze of glory and success. On the other hand, dispensationalism was born in England in the early 1800s bemoaning the latter-day apostasy and ruin of the church. Nevertheless, within Pentecostalism, these two divergent views were merged. Thus, denominations like the Assemblies of God and Foursquare Pentecostals moved away from doctrines like the latter rain teaching and generated official positions against those teachings. It was in the mid-1920s that dispensationalism began to be adopted by non-Calvinists and spread throughout the broader world of Conservative Protestantism.

Dispensationalism appealed to the average person with its emphasis that any average, interested person could understand the Bible without the enlightened help of a liberal education. Once a student understood God’s overall plan for mankind, as administered through the dispensations, he would be able to see God’s hand in history. Thus, dispensational theology made a lot of sense to both Pentecostal and evangelical believers at this point in history.

Post War Development

Fundamentalism/Evangelicalism and Pentecostalism- Charismatic movements spread rapidly in America after the second World War and since dispensationalism was attached to them, it also grew rapidly. Many baby-boomers within Pentecostal and Charismatic churches grew up with dispensationalism and the pre-trib rapture as part of their doctrinal framework. Thus, it would not occur to them that dispensationalism was not organic to their particular brands of restoration theology. Further, as non-Calvinist Fundamentalism grew after the War, especially within independent Baptist circles, there was an even greater disconnect of dispensational distinctives from their Calvinist roots.

We have seen that the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement has a tradition of both Latter Rain/restoration teachings as well as the later rise of a dispensational stream. However, these are contradictory teachings that appear to be on a collision course.

Either the church age is going to end with perfection and revival or it will decline into apostasy, preparing the way for the church to become the harlot of Revelation during the tribulation. It is not surprising to see within the broader Pentecostal/Charismatic movement, since the mid 1980s, a clear trend toward reviving Latter Rain theology and a growing realization that it is in logical conflict with their core doctrine. Many, who grew up on Dispensational ideas and the pre-trib rapture, are dumping these views as the leaven of Latter Rain theology returns to prominence within Pentecostal/Charismatic circles.

Pentecostal/Charismatic leaders like Earl Paulk and Tommy Reid, to name just a couple among many, are attempting to articulate the tension over the struggles of two competing systems. They are opting for the dismissal of dispensational elements from a consistent Pentecostal/Charismatic and Latter Rain theology. Tommy Reid observes:

This great Last Day revival was often likened in the preaching of Pentecostal pioneer to the restoration promised to Israel in the Old Testament. Whereas Dispensationalists had relegated all of these prophetic passages of restoration only to physical Israel, Pentecostal oratory constantly referred to these prophecies as having a dual meaning, restoration for physical Israel, AND restoration for the present day church. WE WERE THE PEOPLE OF THAT RESTORATION, ACCORDING TO OUR THEOLOGY (Tommy Reid, Kingdom Now But Not Yet. Buffalo: IJN Publishing, 1988, pp. xv-xvi. [emphasis in original]).

At the same time, the purge of Dispensationalism from Reformed Christianity, begun in the late 1930s, has been pretty much completed. Typical of this polarization is found in books like John Gerstner’s Wrongly Dividing The Word Of Truth: A Critique of Dispensationalism (John H. Gerstner, Wrongly Dividing The Word Of Truth: A Critique of Dispensationalism. Brentwood, TN: Wolgemuth & Hyatt Publishers, 1991). While admitting on the one hand that a “strange thing about Dispensationalism is that it seems to have had its strongest advocates in Calvinistic churches” (Ibid, 106). Gerstner so strongly opposes dispensationalism, that it has blinded him to the true Calvinist nature of such a God-centered theology. Gerstner claims that he and other Reformed theologians have raised “strong questions about the accuracy of dispensational claims to be Calvinistic” (Ibid, pp. 105-47). It appears that since Dispensationalism arose within the Reformed tradition, as a rival to Covenant Theology, some want to say that they cannot logically be Calvinistic. This is what Gerstner contends. However, in spite of Gerstner’s sophistry on this issue,he cannot wipe out the historical fact that dispensationalism was birthed within the biblical mindset of a clear theocentric theology and by those who held strongly to soteriological Calvinism. The fact that Dispensationalism arose within a Reformed context is probably the reason why the Reformed community has led the way in the criticism of Dispensational theology.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article is to remind modern Dispensationalists and Calvinists of the historical roots of Dispensationalism. It is precisely because Dispensationalism has penetrated almost every form of Protestantism that many today may be surprised to learn of its heritage. In our day of Postmodern irrationalism, where it is considered a virtue to NOT connect the dots of one’s theology, we need to be reminded that the theology of the Bible is a seamless garment. It all hangs together. If one starts pulling at a single thread, the whole cloth is in danger of unraveling.

I personally think that if systematic Dispensationalism is rightly understood then it still logically makes sense only within a theocentric and soteriologically Calvinistic theology. After all, Dispensationalism teaches that it is GOD who is ruling His household, as administered through the various dispensations of history. However, the reality is that Dispensationalism, or elements of Dispensationalism (i.e., pretribulationism, futurism, etc.), have been disseminated throughout a wide diversity of Protestant traditions. Dispensationalism is best seen as a system of theology that sees views God as the Sovereign ruler of heaven and earth; man as a rebellious vice-regent (along with some angels); Jesus Christ is the hero of history as He is saves some by His Grace; history as a lesson in the outworking of God’s glory being displayed to both heaven and earth. Dispensationalism is a theology that I believe is properly derived from biblical study and lets God be God (Article Adapted from Vol. 4: Conservative Theological Journal Volume 4. 2000 (12) (127). Fort Worth, TX: Tyndale Theological Seminary).

About the Author: Dr. Thomas Ice is the Executive Director of The Pre-Tribulational Research Center. He founded The Center in 1994 with Dr. Tim LaHaye to research, teach, and defend the pretribulational rapture and related Bible prophecy doctrines. The Center is currently located on the campus of Liberty University in Virginia.

About the Author: Dr. Thomas Ice is the Executive Director of The Pre-Tribulational Research Center. He founded The Center in 1994 with Dr. Tim LaHaye to research, teach, and defend the pretribulational rapture and related Bible prophecy doctrines. The Center is currently located on the campus of Liberty University in Virginia.

Dr. Ice has authored or co-authored about 30 books, written hundreds of articles, and is a frequent conference speaker. He has served as a pastor for 15 years. Dr. Ice has a B.A. from Howard Payne University, a Th.M. from Dallas Theological Seminary, a Ph.D. from Tyndale Theological Seminary, and is a Doctoral Candidate at The University of Wales in Church History. Dr. Ice lives in Omaha, Nebraska with his wife Janice. Two of their three boys are college graduates and the third is currently in college.